-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

W. G. Liddell, C. R. Carmichael, N. J. McHugh, Joint and soft tissue injections: a survey of general practitioners, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 8, August 2005, Pages 1043–1046, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh683

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives. To determine the type of joint and soft tissue injections carried out by general practitioners (GPs) in the Bath area and factors affecting activity.

Methods. A questionnaire was sent to 360 GPs requesting information on injections carried out during the previous 12 months, referral pathways for injection, barriers to injecting and training.

Results. We received 251 replies. The commonest injections were for tennis elbow, glenohumeral joint, knee, supraspinatus tendonitis and carpal tunnel. The majority of GPs (66.4%) carry out most injections themselves, 26.3% refer to a colleague and 7.3% refer to secondary care. Over half (51%) of all the injections are carried out by 15.6% of the GPs. Factors associated with higher levels of injection activity were: male gender, partnership, more than 10 years’ experience, a special interest in rheumatology or orthopaedics and working in a rural or mixed practice. The most important barriers to carrying out injections were lack of practical training, lack of confidence and inability to maintain skills. Most GPs have been trained on models.

Conclusions. Most GPs carry out some joint and soft tissue injections, but limit themselves to knees, shoulders and elbows. A small highly active group receive referrals from colleagues. Gender and specialist training strongly influence activity. Many, especially female and part-time, GPs find it hard to maintain their skills and confidence. Training targeted at this group, based in practices and using models and other tools, is likely to increase the number of patients receiving timely injections in general practice.

Musculoskeletal disorders represent a large proportion of consultations in primary care, making up some 18% of the workload of general practitioners (GPs) [1]. Many common conditions are effectively treated with joint or soft tissue injections in a primary care setting. However, training in the diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal disorders is recognized to be inadequate [2–4]. This may lead to the under use of potentially beneficial interventions [5] and over-referral of patients with musculoskeletal disorders to rheumatology services [6]. Knowledge of injection techniques has been identified by the Arthritis Research Campaign as a desirable skill for GP registrars [7]. GPs able to carry out injections at the time patients present can potentially reduce the need for referral and consequently waiting time for treatment, travel and inconvenience. Minor surgical procedures carried out by GPs are cost-effective and popular with patients [8].

There are few data on current practice in England with respect to joint and soft tissue injections in primary care. A survey of general practitioners in Northern Ireland showed most injections were carried out by a small number of GPs. Postgraduate training, modality of training and the ability to maintain skills were important determinants affecting the number of injections carried out [9].

The aim of this survey was to establish the level and nature of injection activity in the Bath area and identify the factors that influence this. This information will be used to establish training needs of GPs that might be fulfilled by the local rheumatology service.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was designed to acquire information in five principal areas. These included the demographic characteristics of respondents, the number and types of injections carried out in the last 12 months, perceived barriers to carrying out more injections, the type of training received and preferences for future training. Five-point Likert scales were used to rate the relative importance of the different barriers to carrying out more injections and the level of interest in different types of training. The questionnaire was piloted on 20 GP volunteers who provided feedback on the format and acceptability of the content. As a result of the pilot the questionnaire was reduced in length and changes were made to wording.

The finalized questionnaire was sent to 360 GPs known to be working in practices covered by the Bath area GP Education Programme. GPs who helped with the pilot were not included in the survey. The practices fall under the Wessex and the South Western Deaneries. A reminder and second questionnaire were sent to non-respondents at 6 weeks. The data were collated 4 months after the first mailing. Questionnaires were numerically coded to ensure confidentiality. The results were analysed using SPSS Version 12. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test for differences between groups as the data were not normally distributed.

Results

Response rate

Two hundred and fifty-one replies were received (70% response rate). One questionnaire was blank and three were partially completed. These were not included in the analysis.

Demographics

Male GPs comprised 50.6% of respondents. Partners made up 74.4% of respondents, 15.0% were associates or assistants, 5.7% registrars, 1.6% retainers and 3.6% locums. Practice list size ranged from 1800 to 29 000. The type of practice was described as rural by 20.6% of respondents, urban by 25.9% and mixed by 53.4%. The nature of the GP contract was PMS for 85.3% and GMS for 14.7%. The mean number of sessions worked per week was 4.8 for female and 6.1 for male GPs.

Types of injection

The commonest injections carried out were for tennis elbow, knee joint, glenohumeral joint, supraspinatus tendonitis, carpal tunnel and plantar fasciitis (Table 1).

The frequency and type of joint and soft tissue injections carried out by all respondents in the last 12 months

| Injection type . | Frequency [n (%)] . |

|---|---|

| Tennis elbow | 1002 (14.0) |

| Knee joint | 984 (13.7) |

| Glenohumeral joint | 975 (13.6) |

| Supraspinatus tendonitis | 590 (8.2) |

| Carpal tunnel | 563 (7.9) |

| Plantar fasciitis | 460 (6.4) |

| Acromioclavicular joint | 413 (5.8) |

| Golfer's elbow | 405 (5.7) |

| Trochanteric bursitis | 346 (4.8) |

| Trigger thumb/finger | 315 (4.4) |

| Olecranon bursitis | 263 (3.7) |

| De Quervain's tenosynovitis | 175 (2.4) |

| Carpometacarpal joint | 166 (2.3) |

| Prepatellar bursitis | 143 (2.0) |

| Finger joint | 116 (1.6) |

| Ankle joint | 84 (1.2) |

| Gluteal tendonitis | 69 (1.0) |

| Achilles tendonitis | 38 (0.5) |

| Other injections | 62 (0.8) |

| Total | 7165 (100.0) |

| Injection type . | Frequency [n (%)] . |

|---|---|

| Tennis elbow | 1002 (14.0) |

| Knee joint | 984 (13.7) |

| Glenohumeral joint | 975 (13.6) |

| Supraspinatus tendonitis | 590 (8.2) |

| Carpal tunnel | 563 (7.9) |

| Plantar fasciitis | 460 (6.4) |

| Acromioclavicular joint | 413 (5.8) |

| Golfer's elbow | 405 (5.7) |

| Trochanteric bursitis | 346 (4.8) |

| Trigger thumb/finger | 315 (4.4) |

| Olecranon bursitis | 263 (3.7) |

| De Quervain's tenosynovitis | 175 (2.4) |

| Carpometacarpal joint | 166 (2.3) |

| Prepatellar bursitis | 143 (2.0) |

| Finger joint | 116 (1.6) |

| Ankle joint | 84 (1.2) |

| Gluteal tendonitis | 69 (1.0) |

| Achilles tendonitis | 38 (0.5) |

| Other injections | 62 (0.8) |

| Total | 7165 (100.0) |

The frequency and type of joint and soft tissue injections carried out by all respondents in the last 12 months

| Injection type . | Frequency [n (%)] . |

|---|---|

| Tennis elbow | 1002 (14.0) |

| Knee joint | 984 (13.7) |

| Glenohumeral joint | 975 (13.6) |

| Supraspinatus tendonitis | 590 (8.2) |

| Carpal tunnel | 563 (7.9) |

| Plantar fasciitis | 460 (6.4) |

| Acromioclavicular joint | 413 (5.8) |

| Golfer's elbow | 405 (5.7) |

| Trochanteric bursitis | 346 (4.8) |

| Trigger thumb/finger | 315 (4.4) |

| Olecranon bursitis | 263 (3.7) |

| De Quervain's tenosynovitis | 175 (2.4) |

| Carpometacarpal joint | 166 (2.3) |

| Prepatellar bursitis | 143 (2.0) |

| Finger joint | 116 (1.6) |

| Ankle joint | 84 (1.2) |

| Gluteal tendonitis | 69 (1.0) |

| Achilles tendonitis | 38 (0.5) |

| Other injections | 62 (0.8) |

| Total | 7165 (100.0) |

| Injection type . | Frequency [n (%)] . |

|---|---|

| Tennis elbow | 1002 (14.0) |

| Knee joint | 984 (13.7) |

| Glenohumeral joint | 975 (13.6) |

| Supraspinatus tendonitis | 590 (8.2) |

| Carpal tunnel | 563 (7.9) |

| Plantar fasciitis | 460 (6.4) |

| Acromioclavicular joint | 413 (5.8) |

| Golfer's elbow | 405 (5.7) |

| Trochanteric bursitis | 346 (4.8) |

| Trigger thumb/finger | 315 (4.4) |

| Olecranon bursitis | 263 (3.7) |

| De Quervain's tenosynovitis | 175 (2.4) |

| Carpometacarpal joint | 166 (2.3) |

| Prepatellar bursitis | 143 (2.0) |

| Finger joint | 116 (1.6) |

| Ankle joint | 84 (1.2) |

| Gluteal tendonitis | 69 (1.0) |

| Achilles tendonitis | 38 (0.5) |

| Other injections | 62 (0.8) |

| Total | 7165 (100.0) |

Factors affecting injection numbers

The majority of GPs [164 (66.4%)] carried out most injections themselves, 65 (26.3%) referred most to another GP and 18 (7.3%) referred most patients to secondary care for injection. The median number of injections per GP carried out in the last 12 months was 17.0 (interquartile range 7.0–38.0). For those doing all their own injections the median number was 30.0 (interquartile range 16.0–52.4).

In the last 12 months 86.2% of all GPs had performed at least one injection. Less than one-fifth of GPs (15.8%) had carried out over half (50.5%) of all the injections.

The median number of injections carried out by male GPs (31.0) was significantly greater than females (10.0) (U = 3411.0, P<0.001).

The 22 GPs professing a special interest in rheumatology carried out significantly more injections (median 53.3, interquartile 22.2–100.0) than others (U = 1251.5, P<0.001). There was some evidence that the 16 GPs with a special interest in orthopaedics carried out more injections (median 31.0, interquartile range 17.0–81.9) (U = 1238.5, P = 0.029). Having an interest in sports medicine (21 GPs) did not seem to increase the number of injections (median 27, interquartile range 6.0–49.8) (U = 2131.0, P = 0.457).

Barriers to performing injections

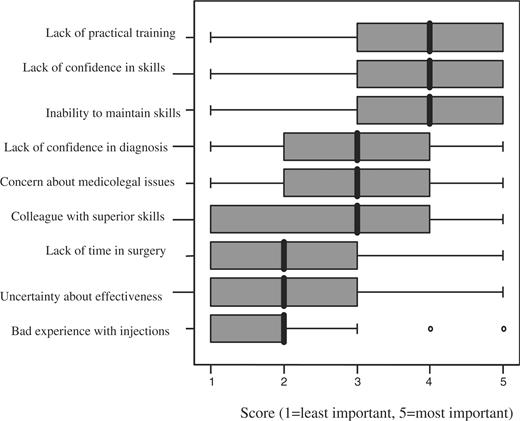

There were 244 responses to this question. Lack of practical training, lack of confidence in skills and inability to maintain skills were rated as the most important barriers to carrying out more injections (Fig. 1).

Perceived importance of different barriers to carrying out more injections. The boxes indicate the lower and upper quartiles and the central line is the median.

Previous training

Most (159, 64.4%) GPs had received training in injection techniques within the last 5 yr. The majority (128, 79.7%) had received this training in a course setting using models. Most of the remainder had received training either in primary care with a GP trainer or in a secondary care clinic. Only 65 (42.2%) rated their training as helpful (level 1–2 on a five-point scale).

Preferred training context

Many respondents expressed enthusiasm for further training in injection techniques and added comments to this effect. When asked about the modality of training the highest level of interest was in training on ‘live’ patients in the rheumatology department [median 3.0 (2.0–4.0)] or in the practice [3.00 (2.00–4.0)] and in practice-based training using models [3.00 (2.0–4.0)]. There was least enthusiasm for web-based training and training using CD-ROMs [2.0 (1.0–3.0)].

Discussion

Our survey produced a good response rate given the reluctance of GPs to respond to questionnaires [10]; this result may be ascribed to the link with developing local educational activities. Information on the number of injections carried out was based on GPs’ own estimates of their activity, which may be a source of bias.

The overall level of injection activity was similar to that found in Roberts et al.'s survey in Sheffield [1], but higher than that found in Northern Ireland, where only 55% of GPs had carried out an injection in the last year [9]. GPs working in rural or mixed practices carry out more injections than urban GPs, perhaps reflecting the easier access for urban patients to secondary care services. A small number of GPs carry out large numbers of injections and inject a wide range of joints. Such GPs have developed an interest in joint injection and have often held post-registration posts in rheumatology or orthopaedics. The role of these GPs may expand further, but the potential for this is limited in smaller practices as most referrals are to colleagues within the same practice.

Female GPs, retainers and locums carry out fewer injections. There are several possible reasons for this. They generally work fewer sessions and see fewer patients. Furthermore, their case mix may be different; female GPs carry out more consultations for gynaecological problems, for example, so that they may see fewer musculoskeletal problems and may have fewer opportunities to build and maintain skills in joint and soft tissue injections.

In our survey lack of training, lack of confidence in skills and inability to maintain skills were the main reasons given for not carrying out more injections. Many respondents added comments indicating their wish for a greater level of skill in injection techniques. Gormley et al. [9] did not mention initial training, but found ‘inability to maintain skills’ was the most important barrier. Roberts et al. [1] highlighted ‘little opportunity to learn’ and ‘not enough opportunity for regular practice’.

These findings highlight a problem faced by all GPs who need to maintain a wide range of clinical skills, many of which they do not regularly use. Ability and confidence in performing clinical skills tend to deteriorate with time unless the skills are exercised regularly [11]. Deterioration may be faster with respect to more invasive techniques such as joint injection. GPs who attract referrals from colleagues are likely to maintain and develop their skills further. An important question arises as to the how often a procedure should be repeated to maintain competence.

More than half of GPs had some form of training in injection techniques in the last 5 yr; of these 12.6% had performed no injections in the last 12 months. Most GPs in the survey had been trained on models. It was not possible to say whether those trained on ‘live’ patients performed more injections or had more confidence; however, it is likely that those who had held posts in rheumatology or orthopaedics had received more ‘on the job’ training with patients and these GPs carried out more injections. The practicalities of training on ‘live’ patients make this type of training harder to access. The changing relationship between patients and health-care providers means that it is less acceptable for patients to be passive, uninformed participants in medical education [12]. Innovative solutions to this problem have been developed for surgical training and these may have a role in helping GPs to develop and maintain injection skills [13, 14]. Such solutions offer the opportunity for practising a procedure repeatedly in a safe environment with feedback available from a skilled tutor. For many procedures high-quality simulation can be achieved by using patients or actors to provide feedback not just on technical performance, but on aspects of communication as well.

The survey has highlighted a need for ongoing training opportunities easily accessible to female GPs and GPs working part-time who encounter particular difficulties in developing and maintaining joint and soft tissue injecting skills. Such training should either involve some practice with ‘live’ patients or use innovative solutions to simulate real clinical encounters. Female GPs working part-time comprise an increasing proportion of the workforce so such training is likely to have a significant impact on the management of musculoskeletal problems in primary care [15].

Future research needs include the development of a solid evidence base regarding the standards and techniques suitable for treating different rheumatic conditions [16]. There is also a need for a better understanding of the competence of GPs currently performing injections and of the most effective methods for GPs to acquire and maintain their skills using new technologies for simulation.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Roberts C, Adebajo AO, Long S. Improving the quality of care of musculoskeletal conditions in primary care.

Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R. Care management of musculoskeletal disorders.

Hay EM, Patterson S, Lewis M, Hosie G, Croft P. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care.

Winters JC, Sobel JS, Groenier KH, Ardenzen HJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Comparison of physiotherapy, manipulation and corticosteroid injection for treating shoulder complaints in general practice: randomized single blind study.

Jolly M, Curtan JJ. The underuse of intra-articular and periarticular corticosteroid injections by primary care physicians: discomfort with the technique.

Arthritis Research Campaign.

Brown JS, Smith RR, Cantor T, Chesover D, Yearsley R. General practitioners as providers of minor surgery: a success story?

Gormley GJ, Corrigan M, Steele WK, Stevenson M, Taggart AJ. Joint and soft tissue injections in the community: questionnaire survey of general practitioners’ experiences and attitudes.

Kaner EF, Haighton CA, McAvoy BR. “So much post, so busy with practice—so, no time!”: a telephone survey of general practitioners reasons for not participating in postal questionnaire surveys.

Arthur W, Bennet W, Stanush PL, McNelly TL. Factors that influence skill decay and retention: a quantitative review and analysis.

Bradley P, Postlethwaite K. Setting up a clinical skills learning facility.

Kneebone R, ApSimon D. Surgical skills training: simulation and multimedia combined.

Kneebone R. Simulation in surgical training: educational issues and practical implications.

Comments