-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Henk Verloo, Arnaud Chiolero, Blanche Kiszio, Thomas Kampel, Valérie Santschi, Nurse interventions to improve medication adherence among discharged older adults: a systematic review, Age and Ageing, Volume 46, Issue 5, September 2017, Pages 747–754, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx076

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

discharged older adult inpatients are often prescribed numerous medications. However, they only take about half of their medications and many stop treatments entirely. Nurse interventions could improve medication adherence among this population.

to conduct a systematic review of trials that assessed the effects of nursing interventions to improve medication adherence among discharged, home-dwelling and older adults.

we conducted a systematic review according to the methods in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook and reported results according to the PRISMA statement. We searched for controlled clinical trials (CCTs) and randomised CCTs (RCTs), published up to 8 November 2016 (using electronic databases, grey literature and hand searching), that evaluated the effects of nurse interventions conducted alone or in collaboration with other health professionals to improve medication adherence among discharged older adults. Medication adherence was defined as the extent to which a patient takes medication as prescribed.

out of 1,546 records identified, 82 full-text papers were evaluated and 14 studies were included—11 RCTs and 2 CCTs. Overall, 2,028 patients were included (995 in intervention groups; 1,033 in usual-care groups). Interventions were nurse-led in seven studies and nurse-collaborative in seven more. In nine studies, adherence was higher in the intervention group than in the usual-care group, with the difference reaching statistical significance in eight studies. There was no substantial difference in increased medication adherence whether interventions were nurse-led or nurse-collaborative. Four of the 14 studies were of relatively high quality.

nurse-led and nurse-collaborative interventions moderately improved adherence among discharged older adults. There is a need for large, well-designed studies using highly reliable tools for measuring medication adherence.

Background

Medication adherence—defined as the extent to which patients take medication as prescribed by their healthcare professionals—is an important aspect of treatment efficacy, healthcare costs and patient safety [1, 2]. Medication adherence also implies the notion of concordance, i.e. a process of shared decision-making between patients and healthcare professionals [3]. According to a WHO report, inadequate medication adherence averaged 50% among patients with a chronic disease [4] and represented a significant problem that led to increased morbidity and mortality, as well as increased healthcare costs [5, 6]. Many older adults suffer from multiple chronic diseases and are treated with numerous medications. They are, therefore, at a high risk of poor adherence, e.g. missing doses, discontinuation, alteration of schedules and doses or overuse [7]. Non-adherence can result in worsening clinical outcomes, including re-hospitalisation, exacerbation of chronic medical conditions and greater healthcare costs [8, 9]. Up to 10% of hospital readmissions have been attributed to non-adherence [6].

Several studies have demonstrated that insufficient medication adherence is common among discharged older adults [9, 10]. Older adults experienced changes in their medication regimen during hospitalisation [11] and in the 1st week following hospital discharge [8]. Such changes, as well as complex treatment plans, tended to decrease medication adherence and could be a reason for a patient's non-adherence. Older adults may also have restarted taking medications that were discontinued during hospitalisation, failed to start new medications initiated during hospitalisation, or taken incorrect dosages [9, 12]. Moreover, medication changes are poorly communicated to the patient at the time of discharge [13]. Older adults are at a particularly high risk of non-adherence in the 1st days or weeks following hospital discharge [9]. Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals, especially community healthcare nurses, to follow-up with older adults early and frequently to keep them adherent to therapy. Nurses are well placed to provide and coordinate adherence-care because they are present in the majority of healthcare settings, are in close physical proximity to patients, and act as interfaces between patients and physicians [14].

Previous studies have shown that interventions such as patient education, the use of medication management tools or electronic monitoring reminders, can help to improve medication adherence and continuity of care among older adults [15, 16]. However, few studies have evaluated the effects of interventions to improve medication adherence after hospital discharge. Our systematic review focuses on the effectiveness of nurse-led interventions to improve medication adherence in older home-dwelling patients who are discharged from hospital; a previous Cochrane review has looked at a broader range of interventions to enhance medication adherence, in a wide range of patient groups [16]. More specifically, there is little evidence on the impact of nursing interventions—whether alone or in collaboration with other health professionals—on medication adherence among discharged older adults [9].

This systematic review aimed to determine whether nursing interventions alone, or in collaboration with other health professionals, were effective in improving medication adherence among recently discharged, inpatient, home-dwelling older adults aged 65 years old or more, when compared with those receiving usual care.

Methods and materials

This systematic review was conducted according to methods in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook [17] and results were reported according to the PRISMA statement [18].

Data sources and search criteria

In collaboration with a medical librarian (B.K.), a systematic literature search was conducted for any articles published up to 8 November 2016, using predefined search terms in Medline via PubMed (from 1946), EMBASE (from 1947), CINAHL (from 1937), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from 1992), PsycINFO (from 1806), Web of Science (from 1900), JBI database (from 1998), DARE (from 1996), Tripdatabase (from 1997), the French Public Health Database (from 1878), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA, from 1970) and clinicaltrial.gov (from 2008).

The syntax consisted of four search themes intersected by the Boolean term ‘AND’. MeSH terms included age-related terms (Aged), medication adherence-related terms (Medication Adherence, Patient Medication Knowledge, Prescription Drug Misuse, Polypharmacy, Drug Therapy, Medication Therapy Management, Pharmaceutical Preparations/Administration and Dosage), nurse-related terms (Nursing, Nursing Care, Nurses, Nurse–Patient Relations, Models of Nursing) and hospital-related terms (Patient Discharge, Continuity of Patient Care, Inpatients, Hospitalisation). The search strategy was then adapted for EMBASE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsycINFO, Web of Science, the JBI database, DARE, Tripdatabase, IPA and clinicaltrial.gov (see Supplementary data 2, available at Age and Ageing online).

In addition to the electronic database searches, a hand search of the bibliographies of all relevant articles was conducted, as was a search of unpublished studies using Google Scholar, Proquest, Mednar and Worldcat, without language restrictions. Finally, a forward citation search of the articles selected was also conducted using Google Scholar.

Study selection

Two authors (H.V. and B.K.) independently screened titles, abstracts and full texts from the literature search to determine their eligibility. Full texts were eligible for review if they were written in English, French or German. Studies included: (i) were either randomised clinical trials (RCTs) or controlled clinical trials (CCTs); (ii) had evaluated the effects of nurse interventions or collaborative interventions with other healthcare professionals on medication adherence compared to a usual-care group and (iii) were conducted among recently discharged (<2 weeks after discharge) older adults (aged ≥65 years old), living at home, and taking at least one prescribed medication for any kind of medical condition. Outcomes were changes in medication adherence during follow-up as measured using different methods [1, 14], i.e. electronic monitors, prescription refills, pill counts, medication adherence tools/questionnaires and patient self-reporting. Disagreements between screeners were resolved by consensus.

Nurse interventions were classified as either nurse-led care and nurse-collaborative care, as provided by Registered Nurses (RN). Based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care taxonomy of health systems interventions [19], we considered patient-level interventions conducted by nurses (education, counselling and teaching; reminder interventions using telephone contact, discharge planning or medication adherence aids, e.g. electronic monitors or pill dispensers; meetings with a healthcare professional in the patient's home). These could be alone or in collaboration with pharmacists or physicians. We also considered interventions at the healthcare-professional level (educational meetings and distribution of educational materials; educational outreach visits with feedback through medication reviews of medical records; monitoring of medication therapy by assessment, adjustment or change of medication; verbal or oral recommendations to pharmacists or physicians; team meetings to discuss care or refer the patient to the physician). Interventions targeting healthcare organisations, legal regulations and financial issues were excluded.

Data extraction and risk of bias in the studies included

Two authors (H.V. and B.K.) extracted data independently, using a specially designed and standardised data extraction form. If necessary, any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with the co-authors (V.S. and A.C.). The information extracted from each study included: (i) study author, year of publication and country; (ii) study characteristics (including study setting and design, duration of follow-up and sample size); (iii) participants’ characteristics (including sex, age, medication and medical conditions); (iv) intervention characteristics (including description and frequency of nursing interventions, and the healthcare professionals involved); (v) usual-care group's characteristics; and (vi) types of outcome measures (including medication adherence rates or score, and self-assessment of medication adherence).

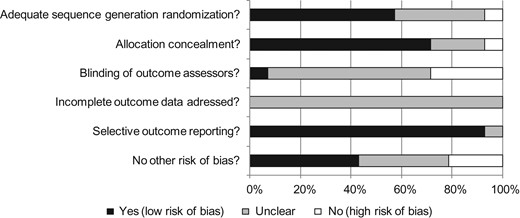

Risk of bias in the studies included

Two authors (H.V. and B.K.) independently assessed the risk of bias for all the studies included, using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [20], a validated tool for RCTs [21–24] based on six domains: adequate sequence randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding of outcome assessors, adequately addressed incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other risks of bias. Each domain was rated as: (i) low risk of bias, (ii) unclear or (iii) high risk of bias. A study was considered of relatively high quality if it had adequate sequence randomisation and a blinding of outcome assessors (i.e. low risk of bias in both domains). Any disagreement in the quality assessment was resolved by consensus.

Results

Results of the search strategy

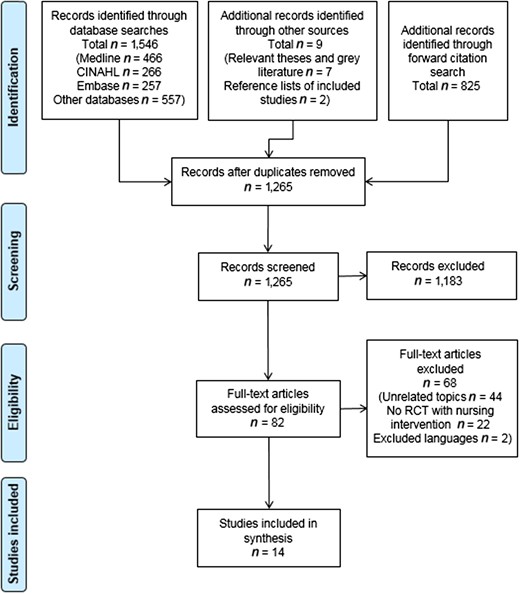

In total, 1,546 records were identified using the electronic search strategy, nine using grey literature and references listed in selected papers, and 825 using the forward citations search. After removal of duplicates, 1,265 records were screened based on title and abstract, and 82 were considered potentially eligible and had their full texts evaluated. A total of 14 studies satisfied the selection criteria and were included (Figure 1).

PRISMA flow diagram summarising the results of the search strategy.

Characteristics of studies and participants

The 14 studies included were conducted on three continents (Europe, n = 5; Asia, n = 2 and North America, n = 7), in seven countries (Canada, China, Denmark, Italy, Israel, Netherlands and the USA), and were published between 1989 and 2015 (Table 1). Eleven studies were RCTs and three were CCTs. Ten RCTs were randomised at the patient level and one at the hospital level (cluster). Overall, interventions involved nurse-led care in seven studies and nurse-collaborative care in seven more.

Characteristics of the studies included

| References, country . | Design . | Setting . | Medical condition . | Study duration (months) . | Type of intervention . | Usual care . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonicelli et al. [34], Italy | RCT | Outpatient clinic | Congestive heart failure | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routinely planed care visits in the outpatient clinic with a nurse |

| Barnason et al. [25], USA | RCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Heart failure | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine discharge procedure for patients with heart failure carried out by a nurse |

| Bisharat et al. [26], Israel | CCT | Hospital with transition care programme | Chronic heart failure | 9 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Discharge counselling by a nurse |

| Eggink et al. [27], Netherlands | RCT | Hospital patients at discharge | Heart failure | 1.5 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routine discharge planning, including information about drug therapy delivered by a nurse |

| Garcia-Aymerich et al. [28], Spain | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Standard discharge procedure for COPD patients |

| Hornnes et al. [22], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Stroke with hypertension | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Stroke unit's standardised discharge routine care |

| Kennedy [21], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge care and information sheet |

| Rich et al. [29], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Congestive heart failure | 1 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Conventional medical care and hospital's standardised discharge protocol and pre-discharge medication instructions |

| Rinfret et al. [23], Canada | RCT | Hospital inpatient follow-up at home | Drug-eluding stent with anti-platelets | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual counselling before discharge |

| Rytter et al. [30], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and municipality care centres | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual care made up of a short patient education session by a nurse prior to hospital discharge |

| Tsuyuki et al. [31], Canada | RCT | Hospital discharge follow-up programme | Heart failure | 6 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual discharge planning |

| Weller [24], USA | CCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge medication education |

| Wolfe and Schirm [32], USA | CCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1.5 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge planning procedure |

| Zhao and Wong [33], China | RCT | Hospital transitional care programme | Coronary heart disease | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine usual-care protocol |

| References, country . | Design . | Setting . | Medical condition . | Study duration (months) . | Type of intervention . | Usual care . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonicelli et al. [34], Italy | RCT | Outpatient clinic | Congestive heart failure | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routinely planed care visits in the outpatient clinic with a nurse |

| Barnason et al. [25], USA | RCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Heart failure | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine discharge procedure for patients with heart failure carried out by a nurse |

| Bisharat et al. [26], Israel | CCT | Hospital with transition care programme | Chronic heart failure | 9 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Discharge counselling by a nurse |

| Eggink et al. [27], Netherlands | RCT | Hospital patients at discharge | Heart failure | 1.5 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routine discharge planning, including information about drug therapy delivered by a nurse |

| Garcia-Aymerich et al. [28], Spain | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Standard discharge procedure for COPD patients |

| Hornnes et al. [22], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Stroke with hypertension | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Stroke unit's standardised discharge routine care |

| Kennedy [21], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge care and information sheet |

| Rich et al. [29], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Congestive heart failure | 1 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Conventional medical care and hospital's standardised discharge protocol and pre-discharge medication instructions |

| Rinfret et al. [23], Canada | RCT | Hospital inpatient follow-up at home | Drug-eluding stent with anti-platelets | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual counselling before discharge |

| Rytter et al. [30], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and municipality care centres | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual care made up of a short patient education session by a nurse prior to hospital discharge |

| Tsuyuki et al. [31], Canada | RCT | Hospital discharge follow-up programme | Heart failure | 6 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual discharge planning |

| Weller [24], USA | CCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge medication education |

| Wolfe and Schirm [32], USA | CCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1.5 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge planning procedure |

| Zhao and Wong [33], China | RCT | Hospital transitional care programme | Coronary heart disease | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine usual-care protocol |

Characteristics of the studies included

| References, country . | Design . | Setting . | Medical condition . | Study duration (months) . | Type of intervention . | Usual care . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonicelli et al. [34], Italy | RCT | Outpatient clinic | Congestive heart failure | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routinely planed care visits in the outpatient clinic with a nurse |

| Barnason et al. [25], USA | RCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Heart failure | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine discharge procedure for patients with heart failure carried out by a nurse |

| Bisharat et al. [26], Israel | CCT | Hospital with transition care programme | Chronic heart failure | 9 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Discharge counselling by a nurse |

| Eggink et al. [27], Netherlands | RCT | Hospital patients at discharge | Heart failure | 1.5 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routine discharge planning, including information about drug therapy delivered by a nurse |

| Garcia-Aymerich et al. [28], Spain | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Standard discharge procedure for COPD patients |

| Hornnes et al. [22], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Stroke with hypertension | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Stroke unit's standardised discharge routine care |

| Kennedy [21], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge care and information sheet |

| Rich et al. [29], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Congestive heart failure | 1 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Conventional medical care and hospital's standardised discharge protocol and pre-discharge medication instructions |

| Rinfret et al. [23], Canada | RCT | Hospital inpatient follow-up at home | Drug-eluding stent with anti-platelets | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual counselling before discharge |

| Rytter et al. [30], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and municipality care centres | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual care made up of a short patient education session by a nurse prior to hospital discharge |

| Tsuyuki et al. [31], Canada | RCT | Hospital discharge follow-up programme | Heart failure | 6 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual discharge planning |

| Weller [24], USA | CCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge medication education |

| Wolfe and Schirm [32], USA | CCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1.5 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge planning procedure |

| Zhao and Wong [33], China | RCT | Hospital transitional care programme | Coronary heart disease | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine usual-care protocol |

| References, country . | Design . | Setting . | Medical condition . | Study duration (months) . | Type of intervention . | Usual care . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonicelli et al. [34], Italy | RCT | Outpatient clinic | Congestive heart failure | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routinely planed care visits in the outpatient clinic with a nurse |

| Barnason et al. [25], USA | RCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Heart failure | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine discharge procedure for patients with heart failure carried out by a nurse |

| Bisharat et al. [26], Israel | CCT | Hospital with transition care programme | Chronic heart failure | 9 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Discharge counselling by a nurse |

| Eggink et al. [27], Netherlands | RCT | Hospital patients at discharge | Heart failure | 1.5 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Routine discharge planning, including information about drug therapy delivered by a nurse |

| Garcia-Aymerich et al. [28], Spain | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Standard discharge procedure for COPD patients |

| Hornnes et al. [22], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Stroke with hypertension | 12 | Nurse-led intervention | Stroke unit's standardised discharge routine care |

| Kennedy [21], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge care and information sheet |

| Rich et al. [29], USA | RCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Congestive heart failure | 1 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Conventional medical care and hospital's standardised discharge protocol and pre-discharge medication instructions |

| Rinfret et al. [23], Canada | RCT | Hospital inpatient follow-up at home | Drug-eluding stent with anti-platelets | 12 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual counselling before discharge |

| Rytter et al. [30], Denmark | RCT | Hospital and municipality care centres | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual care made up of a short patient education session by a nurse prior to hospital discharge |

| Tsuyuki et al. [31], Canada | RCT | Hospital discharge follow-up programme | Heart failure | 6 | Nurse-collaborative intervention | Usual discharge planning |

| Weller [24], USA | CCT | Hospital care with follow-up | Geriatric inpatients | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge medication education |

| Wolfe and Schirm [32], USA | CCT | Hospital and home healthcare setting | Geriatric inpatients | 1.5 | Nurse-led intervention | Usual discharge planning procedure |

| Zhao and Wong [33], China | RCT | Hospital transitional care programme | Coronary heart disease | 3 | Nurse-led intervention | Routine usual-care protocol |

The 14 studies involved a total of 2,028 participants (995 in experimental groups; 1,033 in usual-care groups) aged from 63 to 83 years old and followed-up over a mean of 5.3 months (SD = 4.7; range: 1–12 months). All studies included men and women. The patient groups included were older discharged inpatients with cardiovascular diseases (n = 8), post-surgical interventions in geriatric and internal medicine units (n = 4), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 1) or stroke with hypertension (n = 1).

Characteristics of nurse interventions

All studies employed discharge planning and patient education as usual-care activities to improve medication adherence. These interventions were carried out in hospital and/or at the participant's home (counselling and patient education/teaching). The interventions exclusively delivered by RNs or implemented in collaboration with other healthcare professionals were multidimensional. Hence, some interventions integrated other healthcare professionals and patients through meetings, education sessions or reminders (see Supplementary data 1, available at Age and Ageing online).

The majority of the nurse-led interventions involved comprehensive assessments of medication during home visits, verbal advice, medication education and written factsheets, care plans and medication schedules, and verbal and written reminders by telephone or using electronic devices, mostly done by nurses and by electronic pill dispensers [21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 32, 33].

The nurse-collaborative interventions were more focused around participants’ clinic visits, integrating counselling and comprehensive teaching by a pharmacist or a physician about the importance of medication adherence, and the aid of electronic devices such as weekly tele-monitoring, daily ECG, weighing, medication organisers and electronic patient reminders about medication adherence [23, 26, 27, 29–31]. Two collaborative interventions used medication adjustments by the pharmacist, organised feedback to other healthcare professionals, and proposed social and personal support [27, 30].

Medication adherence

Five studies assessed medication adherence as the primary outcome [23, 26, 29, 32, 34] and nine studied it as a secondary outcome [21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33]. Pill counts [29] were used to measure medication adherence, as were the following standardised, validated instruments: the Brief Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) [25, 27], the Medication Adherence Scale [28], the Medication Error Rating [21], the Medication Possession Rating [26, 31] and the Modified Centre for Adherence Support Evaluation (CASE) adherence index [39]. Self-reported measures [22, 30, 32–34] and the medication pharmacy prescription refill [23] were used in almost half of the studies retrieved (see Supplementary data 3, available at Age and Ageing online).

A 1-month study using pill counts was conducted by a pharmacist visiting patients at home or during patients’ pharmacy visits [29]. Tsuyuki et al. [31] employed pharmacy records over 6 months to calculate the Medication Possession Ratio, documented as one of the most accurate and reliable methods of measuring medication adherence [35]. Barnason et al. and Eggink et al. measured medication adherence over three and one-and-a-half months, respectively, using the BMQ [36]; Garcia-Aymerich et al. employed the Medication Adherence Scale [37] over 12 months; and Kennedy used the Medication Error Rating Tool [38] over 1 month to discriminate between medication adherence and non-adherence. Tsuyuki et al.[31] and Wolfe and Schirm [32] measured medication adherence using the Medication Possession Ratio and the Medication Rating Scale, respectively. Weller employed a weekly/monthly pill dispenser and measured medication adherence over 3 weeks using the CASE adherence index [39]. Self-reporting was based on telephone calls, interviews during home visits or the analysis of participants’ logbooks (see Supplementary data 3, available at Age and Ageing online). Home visits varied between daily [29], weekly [24, 30, 33], and monthly follow-up visits [22, 32], mostly made by a nurse or a pharmacist. Telephone call follow-up and adherence reminders varied from weekly [21, 24, 25, 28, 31, 33, 34], monthly, to three-monthly contacts [26, 27]. One study assessed participants’ weight weekly using an electronic device [31] and Antonelli et al. assessed weekly electrocardiograms (ECG) by tele monitoring [34]. Only four of the 14 studies reported the duration of the interventions [22, 23, 28, 30]. Table 1 presents the nurse-led, nurse-collaborative interventions and the details of the frequency and the durations of the interventions.

Effects of nurse interventions

The diversity of measurement instruments, medical conditions and the complexity of the intervention designs made it difficult to summarise the effects of those interventions on the improvement of medication adherence. In nine studies, medication adherence was higher in the intervention group than in the usual-care group, and the difference reached statistical significance in eight of them. Three out of seven nurse-led interventions [21, 28, 33] and five out of seven collaborative-care interventions [23, 26, 29, 30, 34] significantly improved medication adherence.

Nurse-led interventions among cardiac patients by Zhao et al. [33], COPD patients by Garcia-Aymerich et al. [28], and post-surgical patients by Kennedy et al. [21] were all associated with improvements in medication adherence. No improvements were observed in the studies conducted among stroke patients by Hornnes et al. [22], geriatric patients by Weller [24], or post-surgical patients by Wolf and Schirm [32].

Nurse-collaborative interventions conducted among cardiac patients by Antonicelli et al. [34], Bisharat et al. [26], Rich et al. [29] and Rinfret et al. [23] were all associated with improvements in medication adherence. However, nurse-collaborative interventions among cardiac patients conducted by Eggink et al.[27] and Tsuyuki et al. [31] were not associated with improvements in medication adherence. In the study by Rytter et al. [30] a nurse-collaborative intervention among post-surgical patients was associated with improvements in medication adherence (P = 0.03).

Risk of bias and methodological quality of the studies

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias graph in included studies. In most domains, few studies had a low risk of bias. Only 4 of 14 studies displayed adequate sequence randomisation and a blinding of outcome assessors and were thus considered of relatively high quality.

Risk-of-bias graph in included studies based on review authors’ judgments about each domain of the risk-of-bias tools.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first systematic review to evaluate nurse interventions aimed at improving medication adherence among discharged older patients, based on RCTs and CCTs. In total, 14 studies were included, incorporating 2,028 participants. Interventions were nurse-led in seven studies and nurse-collaborative in seven more. In nine studies, medication adherence was higher in the intervention group than in the usual-care group, and this difference reached statistical significance in eight studies. The five remaining studies showed no difference in medication adherence. However, very few studies were of relatively high quality. We concluded that nurse-led and nurse-collaborative interventions can improve medication adherence among discharged older adults.

This review has several limitations. One limitation was that many of the studies failed to provide sufficient detail to allow a precise assessment of the risk of bias, or the exact nature, frequency and duration of the intervention tested itself. Additionally, intervention and usual-care groups were not always described in sufficient detail. For example, although a study might clearly state that patients received reminders, the means of administering them was not always described, or was only partly described. This also raised the issue, in many of the studies, of an adequate description of the usual-care group. Some studies merely reported that the participants in the usual-care group received usual care, but did not describe what this entailed. If usual care was already performing relatively well, then it would be harder to show any improvement due to the intervention. Since we used the term ‘ageing’ as a Mesh term or keyword in the search strategy, we may have missed some relevant studies.

Another limitation was the difficulty in accurately assessing medication adherence. It is well documented that studies using self-reporting by patients overestimate medication adherence [40]. These studies are at a high risk of bias when the participant is not blinded to the intervention. The lack of blinding is a limitation; it is especially problematic when adherence was estimated using questionnaires. Indeed, patients in the intervention group may have overestimated their self-reported adherence. Although validated questionnaires are available, their accuracy and reliability are often limited and they depend on the context in which they are used [41]. Pill count is a more objective measure, used in some studies, and it is less exposed to bias than methods based on self-reporting. However, most pill counts are done using pill containers that the participant manages alone or brings along to visits to healthcare professionals, and in these circumstances counts can clearly be altered by the participant [42]. Intervention components that could be explored further include newer information and communication technologies used in addition to regular care, and the specific or coordinated roles of allied health professionals. The duration of intervention varies largely from one study to the other. The association between the duration of intervention and the effect on the outcome was not clear.

All the studies included were relatively small, with sample sizes ranging from 40 to 303 participants. Relatively small studies are more likely to miss significant differences in medication adherence, even when the intervention substantially improves medication adherence [43]. If clinical trial studies need hundreds or thousands of participants to show that interventions improve medication adherence over usual care, then it is unlikely that improving medication adherence among older patients will have a substantial effect on major health outcomes [43]. Innovative ideas to improve medication adherence should be tested in much larger trials in order to document their effects on clinically important outcomes (including adverse effects), their feasibility in everyday practice settings, and their sustainability.

Finally, the lack of substantial evidence could be explained by the fact that we do not understand exactly what medication adherence problems consist of in sufficient detail. Frameworks to assist the development of complex interventions, therefore, advise preparatory assessments involving patients and other stakeholders, in order to better understand the problems and the context. More objective measures of medication adherence are needed to determine intervention effects accurately, and investigators should make use of best-in-class adherence measures, such as prescription monitoring. Researchers should invariably design studies to minimise the risk of bias and should report their procedures clearly.

Despite an extensive search, we may have missed some trials that met all of the present study's criteria. We identified 14 studies evaluating the effect of nurse interventions on medication adherence among discharged older patients. Overall, this systematic review was conducted using high methodological standards, and it is, therefore, highly credible. However, due to the important heterogeneity between studies (design, type of intervention) and their relatively low quality, the level of confidence in the true effect of the nurse interventions on medication adherence is low. Therefore, there is still a need for large, well-designed RCTs using highly reliable tools. Of note, non-adherence is also of concern among younger patients, notably those with chronic psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and major depression. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic review evaluating the effects of nurse interventions to improve medication adherence at the time of discharge among this type of patients.

Conclusion

This systematic review examined the effects of nurse-led and nurse-collaborative interventions to improve medication adherence among discharged home-dwelling older adults. The complex nurse-led and nurse-collaborative interventions retained for this study tended to improve the medication adherence to long-term medication prescriptions among home-dwelling older adults. However, very few studies were of a relatively high quality, thus limiting our confidence in the true effect of these interventions. There is, therefore, a need for further well-designed studies involving large samples and using highly reliable tools, for example, innovative e-health technologies (telephone applications) combined with pill counts to measure medication adherence among home-dwelling older adults.

Nurse interventions to improve medication adherence.

Insufficient medication adherence is common among discharged older adults.

Improving medication adherence among recently discharged inpatient.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Age and Ageing online.

Authors’ contributions

Study design and concept: H.V. and V.S. Writing of study protocol: all authors. Data acquisition: H.V., B.K. and T.K. Data analysis and interpretation: H.V., A.C., T.K. and V.S. Article drafting: H.V. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: H.V., V.S., A.C., B.K. and T.K. Statistical analysis: A.C. and T.K. All authors revised the article for important intellectual content and gave their final approval for the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No external funding was implicated in this systematic review.

Comments