How this fits

• There are widespread unexplained variations in activity and outcome between general practices.

• Large numbers of practices take part in undergraduate teaching (41%), postgraduate training (29%), research (33%), enhanced clinical data collection (Scottish Programme for Improving Clinical Effectiveness (SPICE)) (31%) and the service development activities supported by the Scottish Primary Care Collaborative (SPCC) (33%).

• Practice size was the main determinant of optional participation; deprivation had no overall effect, but was associated with lower levels of participation in postgraduate training.

• About 18% of practices taking part in no optional activities achieved significantly fewer QOF points than the 53% of practices taking part in two or more activities (P < 0.001).

• Variation in the uptake of optional activities by general practices may indicate cultural and organisational factors within practices, which are also associated with the volume and quality of care.

Introduction

General practices are mostly consumed in dealing with the day-to-day demands of patients who require first or continuing contact with the National Health Service. In recent years, they have also been pre-occupied with meeting the incentivised targets of the new General Medical Services (GMS) contract. Most practices also take part in optional activities concerned with the future development of general practice and primary care, including education, research, enhanced information systems and health service initiatives. Previously, we have shown that participation in optional activities is socially patterned, with practices serving deprived areas being much less likely to take part in additional activities (Mackay et al., Reference Mackay, Sutton and Watt2005). In this study, we investigate in more detail the nature, extent and correlates of such activity by general practices in Scotland.

Methods

Data on the number of practices in Scotland in 2005, and the age and gender of general practitioners (GPs) and practice dispensing status in 2004 were obtained from the Information Services Division (ISD), National Health Services (NHS) National Services Scotland. Practices were categorised according to the number of whole time equivalent (WTE) GP principals in 2003 (such data not being available after then): single-handed (up to 1.0 WTE GP); small (1.1–3.0 WTE); medium (3.1–5.0 WTE) and large practices (⩾5.1 WTE).

ISD also supplied data on training practices for 2006 (defined as those practices with at least one GP who is an approved trainer). The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) (Scotland) provided data on practices that had received the Quality Practice Award (QPA) by 2005 or who were participating in the SPICE in 2006. Information on practices participating in the Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN, formerly the Scottish Practices and Professionals involved in Research) was supplied by the Scottish School of Primary Care. Heads of University departments of general practice provided information on general practices taking part in undergraduate medical teaching in 2007, whereas the Scottish Primary Care Collaborative (SPCC) provide data on the number of practices which had taken part in its programmes by 2006.

The level of socio-economic deprivation in the practice population was defined using a modified measure of the 2006 Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), based on composite measures of income, employment, education, housing and crime (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2006/10/13142913/0) (excluding domains for health and geographical access), and providing modified SIMD scores for 6505 Scottish data zones The eight category Scottish Executive Urban Rural Classification measure (Scottish Executive, 2004) was used to identify urban and rural practices by assigning practices to the category which contained the largest proportion of their registered population at September 2002.

We identified the numbers of points achieved by 998 practices taking part in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2006/07, linking ISD data sets to obtain a comprehensive description of practice characteristics for every general practice in Scotland.

General practice populations were ranked on the basis of the average SIMD score of all patient postcodes in the practice list using the modified version of the 2006 SIMD. The ranked list was then divided into ten groups of equal population size, from decile 1 (least deprived) to decile 10 (most deprived). On average, each decile comprises 531 000 people and is served by between 89 and 128 general practices. Practices, could in theory participate in up to six activities but as the number of practices doing so was small we used four or more activities as a cut-off point for the purposes of tabulation. However, for regression analysis the actual number of activities undertaken was used.

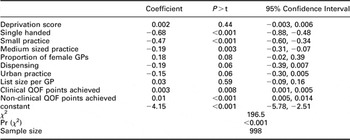

We used cross-tabulations to look separately at the associations between deprivation, rurality and practice size and the number and type of activities, restricting the analysis of practice size to urban practices (since practice size in such settings is a matter of choice). We used a binomial proportion test to examine differences in participation rates between the different groups of practices. Poisson regression analysis was used to identify the determinants of number of activities in relation to GP gender, practice size, QOF points achieved, deprivation, list size per GP and dispensing status (Table 5).

Results

The most popular optional activity was undergraduate medical teaching, which involved 42% of all general practices (Table 1). About a third of practices took part in postgraduate GP training (29%), research (33%), SPICE (31%) and the activities of the SPCC (33%). The RCGP Quality Practice Award was a minority activity, involving only 5% of practices.

Table 1 Participation and QOF points by deprivation

QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework; SIMD = Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation; SPICE = Scottish Program to Improve Clinical Effectiveness; GP = general practitioner; SPCRN = Scottish Primary Care Research Network; SPCC = Scottish Primary Care Collaborative; QPA = Quality Practice Award.

Row percentages in brackets.

QOF data are for 2007.

Table 1 shows that the practices serving the most affluent tenth of the population are more likely to participate in postgraduate training and the QPA scheme than practices serving the most deprived tenth of the population. Conversely, practices serving the most deprived areas were more likely to take part in the service development activities of the Primary Care Collaborative.

The 528 practices serving the more affluent half of the population were more likely than the 503 practices serving the more deprived half to take part in postgraduate training (35% versus 22%, P < 0.001), undergraduate teaching (44% versus 41%, not significant (ns)) and SPICE (33% versus 28%, ns), but less likely to take part in research (30% versus 36%, ns) and the activities of the SPCC (30% versus 37%, P = 0.03). QPA was a minority activity (5%) in all areas (Table 1).

Practices serving populations across the socio-economic spectrum achieved very similar levels of points in the QOF, for both clinical and non-clinical domains, with less than 1% variation between the average levels achieved by practices serving deciles of deprivation (Table 1).

On average, the 268 most rural practices were more likely than the 753 other practices to take part in SPICE (34% versus 30%, ns), but less likely to take part in research (18% versus 39%, P < 0.001), postgraduate training (22% versus 31%, P = 0.004), undergraduate teaching (38% versus 43%, ns) and QPA (2% versus 6%, P = 0.01) (Table 2). Participation in SPCC activities was similar in both types of area (32% versus 34%, ns).

Table 2 Participation by rurality and practice size

SPICE = Scottish Program to Improve Clinical Effectiveness; SPCRN = Scottish Primary Care Research Network; SPCC = Scottish Primary Care Collaborative; QPA = Quality Practice Award.

Row percentages in brackets.

Not all practices could be allocated a size as WTE data were missing.

1. Total is 1,021 because of ten practices not being classified.

Single-handed practices, comprising 12% of all practices in urban areas, were least likely to take part in every optional activity (Table 2). Within the 658 group practices in urban areas, there was a strong association between increasing practice size and participation in postgraduate training, undergraduate teaching and QPA, but no association between practice size and participation in SPICE, research or SPCC programmes (Table 2). Single-handed and small practices also achieved fewer QOF points.

The proportion of practices taking part in two or more optional activities increased from 24% of single-handed practices, to 45% of small practices, 64% of medium-sized practices and 78% of large practices. Conversely, the proportion of practices taking part in no activities increased from 6% of large practices to 10% of medium practices, 20% of small practices and 39% of single-handed practices (Table 2).

The average number of points achieved in the QOF ranged from 960.6 by the 18% of practices taking part in no optional activities, to 972.7 by 29% of practices taking part in one activity (P = 0.02 compared with no optional activities), 983.7 by 25% of practices taking part in two activities (P < 0.001 compared with one activity) and 984.7 in 28% of practices taking part in three or more activities (P = 0.63 compared with two activities). Although, the lowest average scores (<960) were achieved by the most deprived practices taking part in no optional activities, there was no association in any of the other activity groupings between the number of points achieved and the socio-economic status of practice populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) points achieved by practices serving quintiles of deprivation, by number of optional activities. Quintile 1 is least deprived, while Quintile 5 is the most deprived. Note: figures on top of columns are numbers of practices.

Table 4 shows the pairwise correlation coefficients between number of activities undertaken and deprivation, QOF points achieved, practice size, proportion of female GPs and age of GPs in a practice. There is a negative relationship between deprivation and number of activities undertaken but this association is not significant. QOF points achieved is positively and significantly associated with the number of activities undertaken as is large practice size. Single-handed and small practices undertake a significantly lower number of activities.

Table 3 QOF points by practice size in urban general practices taking part in three or more and less than two optional activities

QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Table 4 Correlation coefficients between number of practice activities and practice characteristics

QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework; GP = general practitioners.

P < 0.05, **P < 0.001

Number of practices in each analysis is shown under coefficients.

Controlling for all these factors simultaneously, Table 5 shows that the most important driver of the number of activities undertaken by a practice is size with single handed, small and medium sized practices all undertaking a significantly lower number of activities than larger practices (P ⩽ 0.003), and achieving fewer QOF points. Deprivation appears to have no effect; nor does the proportion of female GPs and dispensing status.

Table 5 Poisson regression analysis of number activities on practice characteristics

QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework; GP = general practitioners.

Deprivation is based on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2006.

Discussion

In an earlier study, we reported lower levels of participation in optional activities by general practices serving deprived areas, based on (i) analyses of participation in postgraduate training and personal medical services and (ii) RCGP quality initiatives, practice accreditation and the SPICE. The current analysis includes new information concerning undergraduate teaching, research in primary care, participation in the SPCC and performance in the QOF of the new GMS contract, and is the first to investigate the association between participation in optional activities and achievement in national quality performance targets.

The strength of the study is that it is based on 1031 general practices in Scotland, comprising a complete national primary care system, and brings together a novel collection of data on practices’ optional activities. For practical reasons, these data were collected at different times over a 4 year period. It is important to note that data on the number of WTE GP per practice ceased to be collected at a national level after the introduction of the new GMS contract in 2004. Analysis of more recent data is desirable but not currently possible.

Although some practices may be involved in other types of optional activity, we believe that the collated data set provides robust and comprehensive evidence of the nature and extent of most of the optional activity undertaken by practices in Scotland during this period. If the recording period had extended after 2007, the figures for participation in research and the SPCC would have been higher, as both schemes have recently expanded.

With this larger and later data set, a different picture emerges from our original study, in which deprivation has a less clear effect. Careful interpretation is needed, however, because of the heterogeneity of practice circumstances and the different nature of optional activities, including what they require of a practice, what practices gain by taking part, financial considerations and the types of support provided for participating practices (Box 1 for description of optional activities).

Box 1 Optional activities

The epidemiology of voluntary participation

The most popular optional activity is undergraduate teaching, which is generally considered to be professionally rewarding, collegiate and enjoyable, and which has expanded considerably in the last decade, as teaching involving GP and general practices has taken up an increasing proportion of new undergraduate curricula and NHS funding (service increment for teaching, SIFT and additional cost of teaching, ACT) has been provided to meet service costs. In general, undergraduate teaching is spread evenly between affluent and deprived and between rural and urban areas.

The lower rates of participation in optional activities by rural practices, for all activities except involvement in the SPICE programme, could be an effect of distance from co-ordinating centres, but may also be due to the effect of practice size. In the regression analysis of factors affecting participation, including practice size, we restricted analyses to non-rural practices, in which the size of the practice is a matter of choice and is not determined by physical constraints of geography and demography.

The dominant effect of practice size, and the disappearance in the regression analysis of the apparent effects of deprivation, dispensing status female GPs is perhaps not surprising, given the greater ability of larger practices to provide lead GPs for different activities and to accommodate additional activity within the work of larger and better resourced organisations.

The absence of an overall effect of deprivation on participation in optional activities in this analysis, compared with our earlier publication, is most likely because of the different activities included in the two analyses. Postgraduate training remains less prevalent in deprived areas (although steps have been taken to address this more recently). The high prevalence of participation in research and in the activities of the SPCC by practices based in deprived areas may be due to their proximity to strong local centres co-ordinating such activity in the Glasgow area, where severe deprivation in Scotland is concentrated.

Optional activities and variations in the quality of care

Although the differences in the number of QOF points achieved by non-participating and participating practices are not large in absolute terms (24.1 points between practices taking part in no activities compared with those taking part in three or more), they are large in relation to the generally small range of variation in QOF points achieved by practices in Scotland as a whole (inter-quartile range: 26.6 points). The main finding is that non-participating practices tend to be smaller and achieved the fewest QOF points irrespective of the socio-economic status of the population served.

Although there are likely to be a great many different local explanations why practices do and do not take part in specific optional activities, and achieve different levels of QOF points, the overall observation, that a fifth of practices take part in no optional activities, while over a half take part in two or more, with a significant difference in QOF points achieved by these two groups of practices, seems worthy of further investigation as a possible indicator of cultural and organisational factors within practices that constrain the volume and quality of the services which they are able to provide.

Our findings relating practice size, optional activities and achievement in the QOF are based on urban practices (excluding Scotland’s distinctive element of having many small practices in remote and rural locations) and may be relevant to urban general practice in other countries. A distinctive feature of general practice in Scotland that it does not have the large, commercially driven types of practice which have been encouraged by Government policy in England, and whose commitment to optional activities is not known.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Heads of University departments of general practice in Scotland who provided information on undergraduate teaching, Catherine Buchanan for information on SPCC collaboration, RCGP Scotland for information on participating in SPICE and QPA and Lucy McLoughlin for information on practice participation in the SPCRN.

Funding Bodies

Daniel F. Mackay is funded by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and the Glasgow Centre for Population Health.

Competing Interests

None.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study.