Abstract

In the setting of the coronavirus pandemic, medical schools across the world transitioned to a remote learning curriculum with the challenge of developing innovative methods to teach clinical skills. During the pandemic, we designed a 2-week remote clinical skills mini-course for third year medical students. The focus was on clinical reasoning, counseling, and the following the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs): 1 (history and physical exam), 2 (prioritize a differential diagnosis), 3 (recommend and interpret diagnostic tests), and 5 (document a clinical encounter). A multi-modal approach included large and small group virtual case-based discussions, a teaching TeleOSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination), and feedback on patient note skills. Students were asked to self-assess their skills before and after the course based on the core EPAs, counseling skills, and overall preparedness for United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Skills exam. Students demonstrated statistically significant increases in mean self-rated scores in all areas except interpreting results of basic studies. They found the teaching TeleOSCE and feedback on their notes the most useful. Future curricula will consider integration of peer-peer remote OSCE practice sessions as well as faculty feedback for individualized learning plans. Lessons learned will be useful for remote structured clinical skills courses in the setting of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical schools across the world grappled with sudden transitions to remote learning in the face of sheltering and physical distancing decisions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical students in hard-hit areas during the pandemic were promptly removed from clinical rotations, mainly due to a national shortage of personal protective equipment. The biggest challenge was the teaching of clinical skills without direct patient contact. This was a critical transition for medical education. Most applied experiential learning for clinical reasoning occur at the bedside of patients during clinical rotations. With loss of this re-enforcement, there is an imminent need to continue the practice and development of these key doctoring skills. When we designed this course, the national decision to temporarily suspend the USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills examination had not been made, so the course was also focused on preparing the students for this graduation requirement. In addition, there were no clear plans for a return date for our Year 3 and 4 medical students on clinical rotations. Thus, we sought to develop a 2-week remote clinical skills course, focusing on the following core areas:

-

1.

AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency[1]

-

a.

EPA1: Gather a history and perform a physical examination

-

b.

EPA2: Prioritize a differential diagnosis following a clinical encounter

-

c.

EPA3: Recommend and interpret common diagnostic and screening tests

-

d.

EPA5: Document a clinical encounter in the patient record

-

a.

-

2.

Clinical reasoning skills

-

3.

Counseling of patients

While a national survey of medicine clerkship directors demonstrated > 75% believed teaching concepts of clinical reasoning was important/extremely important in the clinical years and 87.3% in the clinical clerkships, most institutions lacked structured clinical reasoning sessions [2]. Over the last several years, expanded clinical reasoning curricula have been published, which include a wide variety in duration from single sessions to longitudinal curricula as well as timing in medical school, with some focused solely in pre-clerkship years and others now expanding into the clerkship years [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Delivery of clinical reasoning skills has also varied from computer-based simulations of a clinical scenario to small group case-based discussions and actual patient encounters [9].

We conducted a literature review to identify remote courses that have been used to teach clinical skills. For medical students, we found only a handful of articles on teaching clinical skills remotely, all focusing on the TeleOSCE itself. All utilized standardized patients. However, studies varied in medical school year, focus of the skills assessed, and level of assessment/feedback (formative and summative) [10,11,12]. While there are courses designed to teaching clinical reasoning skills, we did not find virtual courses covering the AAMC EPAs. We created a more robust and holistic approach to a remote clinical skills course. The 2-week entirely remote course combined traditional didactics, a large group OSCE practice session, small group case-based discussions, and a teaching TeleOSCE. We hypothesize that this course will improve the students’ self-reported confidence in clinical reasoning skills. Here, we describe outcomes of the first mini-course pilot.

Materials and Methods

Sixty senior 3rd year medical students enrolled in the clinical skills remote mini-course. The 3rd year class had a total of 183 students at the time. The students had completed the majority of their 3rd year clerkships. The mini-course consisted of an orientation with introduction to clinical reasoning, large group OSCE practice session, small group case-based discussions, and a virtual teaching TeleOSCE.

We used a pre-post course survey for students to self-assess their ability on a variety of areas including obtaining a history, demonstrating clinical reasoning skills, synthesizing essential information to propose differential diagnoses, counseling a patient, and their overall preparedness level for USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills. The questions for the self-assessment were all adapted directly from the AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency Faculty and Learners’ Guide1 from the objectives under “Functions.” An additional question on counseling was added. On the post-survey, students were also asked to note areas for improvement, strengths, and which components they found useful (able to select more than one).

An outline of the mini-course included:

-

Introduction to Clinical Reasoning: During this virtual WebEx session, short cases with the same chief complaint were reviewed with students, highlighting key signs/symptoms that would change the differential diagnosis despite the same chief complaint. This was meant to reinforce illness scripts/patterns for diagnoses, highlighting key differentiating factors.

-

Small Group Case-Based Discussions: All students completed two different cases with the same chief complaint of altered mental status. The sessions were held virtually via WebEx. Illness scripts/patterns were discussed as well as relevant physical exam and diagnostic workup. Each case integrated at least two different specialties.

-

Family Medicine and Internal Medicine

-

70-year-old F with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus with confusion and memory loss

-

-

Neurology and Obstetrics/Gynecology

-

25-year-old F post-partum with new-onset generalized tonic-clonic seizure

-

-

Pediatrics and Family Medicine

-

3-year-old M with acute altered mental status

-

-

Psychiatry and Surgery

-

82-year-old F post-op from femoral neck fracture, now with acute altered mental status

-

-

-

Large Group OSCE Practice Session: Students were broken into groups of 20 with 1 faculty preceptor per group. Each group collectively reviewed an OSCE case, allowing it to unfold in real time (held via WebEx). Similar to a summative OSCE case, students received the door instructions; then as a group they took turns asking appropriate questions, developing their differential diagnoses, and walking through appropriate counseling, including diagnostic/follow-up plan.

-

Submission of Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) style notes: We encouraged students to use readily available Step 2 Clinical Skills cases via board review books and utilize those to complete a minimum of six notes for additional practice. Faculty then provided formative feedback on two of the six notes. A counseling section was added to the template for each note, requiring students to write out the format and content of their counseling based on the case’s differential diagnoses. All notes were submitted within the learning management system, Canvas, with feedback from faculty provided directly within Canvas as well.

-

Teaching TeleOSCE: Each student participated in one teaching OSCE case, a young adult with chief complaint of fatigue. The differential included depression, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and anemia, with the most likely diagnosis of depression. This was done remotely via audio only; video was not used for this case to simulate the phone case at the national boards. Residents in pediatric and psychiatry played the role of standardized patient. Students received the door instruction at the time of the encounter with 15 min in total to complete the history and counsel the patient on differential diagnoses and next steps. Subsequently, the resident had 10–15 min to provide immediate feedback to the student on content of the interview as well as communication skills, using the Arizona Clinical Interview Rating (ACIR) scale as a guide [13]. The feedback was all formative with no numeric grade assigned.

-

Individualized Learning Plan: At the end of the elective, students were asked to reflect on the feedback they received from their clinical skills (case-based discussions, TeleOSCE, and notes) and create a structured learning plan with objectives and an action plan. All individualized learning plans were submitted within the learning management system, Canvas.

At the end of the elective, students were asked to self-assess again on the same content areas noted above as well as their overall preparedness for Step 2 clinical skills and given an opportunity to provide feedback on strengths as well as areas for improvement for the elective. All data were paired. The rating descriptions (area for strength, satisfactory, and strength) were translated into numeric ratings of 1, 2, and 3. The paired pre- and post-survey data were analyzed via XLSTAT using the Sign test with a p value of < 0.05 considered significant.

This study was approved by the Rutgers Institutional Review Board.

Results

A total of 58 senior 3rd year medical students completed both the pre- and post-surveys (Table 1). All ratings reflect students’ self-assessment. Two students were excluded as they had either completed only the pre-survey or post-survey respectively.

Over 50% of students noted an increase in their self-assessment of clinical reasoning skills in gathering demonstrating clinical reasoning in gathering focused information relevant to a patient’s care (mean change 0.62; scale 1–3), synthesizing essential information from the patient to propose a differential diagnosis (0.55), providing rationale for decision to order tests (0.50), counseling the patient on most likely diagnoses, next steps, and follow-up plan (0.53). There was a statistical difference in the mean change with a p < 0.05 for all areas with the exception of interpreting results of basic studies (0.16). The remaining areas had mean changes ranging from 0.29 to 0.48: perform a clinically relevant physical exam (0.29), demonstrate patient-centered interview skills (0.31), recommend first-line cost effective screening tests (0.33), obtain a complete and accurate history (0.36), document a problem list, differential diagnosis, and plan (0.41), and prioritize and synthesize information in a cogent narrative (0.48). Furthermore, 69% of students noted an increased rating in how prepared they feel for USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills with a mean change of 0.78 (scale of 1 to 5).

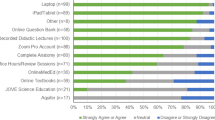

When asked which components students found useful (allowed to select more than one), 82.8% of students found teaching TeleOSCE useful; 77.6% the feedback on the notes, 60.3% the clinical reasoning small group session, 48.2% the large group OSCE practice session; and 13.8% the individualized learning plan.

In terms of how to improve the elective, 20% of students wanted more teaching OSCE cases and scenarios; some suggested having structured sessions with peers to practice. Students also found writing the CS style notes helpful. A general theme was also the feedback provided throughout all course activities: feedback on the Step 2 CS notes via the online learning platform; feedback from the resident during the virtual OSCE, and real-time feedback in the large group OSCE practice session. In addition, students felt the requirement to submit 6 notes, even though only 2 were provided written feedback, “forced” them to use them for practice, which also helped build their differential diagnosis skills. Students also found the structured practice for counseling helpful as well. When asked regarding the effectiveness of the remote instruction versus in-person, students highlighted the need to practice physical exam skills.

Discussion

We implemented a 2-week remote clinical skills mini-course for sixty senior 3rd year medical students. The multi-modal approach was well received by students and created learning opportunities for varied learning styles. Highlights of the mini-course included virtual small and large group case-based discussion to build clinical reasoning skills, feedback on Step 2 CS style notes, and the culmination of the learning in a teaching TeleOSCE utilizing residents as the standardized patients. Utilizing residents as the standardized patients allowed for more robust feedback on the clinical content and clinical reasoning components of the case.

In creating this mini-course, we focused on several of the AAMC Core EPAs, including obtaining appropriate history and physical exam as well as documenting the clinical encounter, which includes recommending appropriate diagnostic tests and the overall management plan. Clinical reasoning is defined as “the mental process that happens when a doctor encounters a patient and is expected to draw a conclusion about (a) the nature and possible causes of complaints or abnormal conditions of the patient, (b) a likely diagnosis, and (c) patient management actions to be taken” [14]. Thus, clinical reasoning is the foundational aspect to the development of the core EPAs. Often, the term clinical reasoning is applied loosely and broadly within a curriculum, such as on inpatient teaching rounds or morning report sessions. The “how to” engage in deliberative clinical reasoning steps is important, especially for early-level learners such as medical students. Therefore, teaching of clinical reasoning skills using a framework with a structured approach may be valuable. Counseling of the patient requires the clinician to have an appropriate differential and diagnostic plan. Studies in clinical reasoning show students have difficulty with closure, including need for additional history and physical exam information, inability to utilize presented information, and uncertainty of their clinical reasoning skills. Furthermore, students may have a tendency to “anchor” on their first diagnosis and thus not incorporating new data into their differential diagnosis. Finally, students misinterpret data due to either factual errors (i.e., misinterpreting data) or limitations in their own knowledge [15]. Utilizing a structured approach with a foundation in the EPAs was essential in creating a robust curriculum. EPAs created a framework for both the didactics and small group sessions, as well as assessment tools.

Thus, in the setting of the pandemic, when direct in-person patient care is not always possible, it is essential to create a remote course focusing on clinical reasoning skills with a foundation in telehealth. Our senior 3rd year medical students demonstrated statistically significant improvement in their self-assessment of core clinical skills after completion of the 2-week remote clinical skills elective. The most significant improvements were noted in demonstrating clinical reasoning in gathering focused information, synthesizing essential information from the patient to propose a differential diagnosis, providing a rationale for decision to order tests, and counseling the patient on most likely diagnoses, next steps, and follow-up plan. This is not surprising given the focus of the elective was on these core skills. Smaller yet still statistically significant increases were seen in all areas of self-assessment in the post-survey with the exception of interpreting results of basic studies.

While the overall mean change in the pre- and post-surveys was modest, this likely reflects a combination of outcomes including some students actually highlighting their deficiencies through this process and thus their ratings stayed the same or even decreased in some instances. The areas with 10% or greater of students noting a decrease in their self-assessment included obtaining a complete and accurate history, demonstrating patient-centered interview skills, recommending first-line cost effective screening, providing rationale for decision to order tests, interpreting results of basic studies, counseling the patient, and documenting a problem list, differential diagnosis, and plan. Decreases in self-assessment may be seen as a positive outcome. Given the ongoing feedback in a variety of modalities, this forced students to consciously and thoughtfully reflect on their own performance, highlighting areas for improvement. Admittedly, interpreting results was not directly addressed during this elective and should be added to future electives. While recommending and interpreting common diagnostic tests is often discussed on clinical rounds, similar to other aspects of clinical reasoning, students need a structured approach in tackling this critical EPA. This could be easily incorporated into the small group case-based discussions as well as feedback on written notes. The notes within this elective were primarily focused on USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills and thus students were not required to justify their diagnostic workup. In the future, we plan to incorporate the rational use of diagnostic investigations within the note with individual feedback provided by faculty.

Overall, a higher percentage of students found the TeleOSCE helpful compared to the large group OSCE practice session. This reflects the need for a student to have autonomy to practice their skill set as well as receiving immediate feedback. While the OSCE practice session is a helpful adjunct and can be done on a larger scale (15–20 students/group), it does not negate the need for 1:1 OSCE cases.

In converting an existing OSCE case to a remote/telemedicine case, faculty should consider the following: type of encounter (videoconferencing versus phone), technology used (video conferencing platform versus actual telemedicine platform used at institution), adapting the “door” instructions and grading rubrics. For this mini-course, we chose to do phone encounter as opposed to videoconference as this is what was previously used on USMLE Step 2 Clinical Skills Exam. For future TeleOSCEs, both video and phone encounters can be useful to mimic what happens in real life (i.e., video not working or patient does not have access to camera). Utilizing residents as the standardized patients was incredibly helpful in order to provide content-specific feedback on history, clinical reasoning, counseling, and communication skills. Orientation must be held in advance to discuss objectives of case as well as how to provide appropriate feedback. However, acting may not be their strength as in traditional standardized patients.

Overall, only 13.8% of students found the individualized learning plan (ILP) useful. Students were required to submit objectives and an action plan based on the feedback they received from faculty in small and large group case discussions, the residents in the teaching TeleOSCE, and feedback on their notes. Students were provided a template with sample objectives and action plan and asked to submit their final ILP in our on-line learning management system. The low rating is likely a combination of the need for a 1:1 meeting with faculty to summarize the feedback and provide guidance on the ILP itself as well as the current pandemic state where students were unsure when they would be returning to clinical rotations and thus struggling with how best to practice at home without actual patients.

The key to success for this elective was ongoing feedback in every form. While this can be time consuming on the part of the faculty, utilizing residents as part of medical education electives be paired with faculty led feedback to create a more robust system. Furthermore, peer-driven practice opportunities should be explored further. Several students noted that the board review books are difficult to practice alone without a partner to review cases with. Development of structured, peer to peer TeleOSCEs may provide additional practice and learning opportunities, which would then allow students to practice all of these components and provide feedback to each other. This needs to be paired with resident and/or faculty components of feedback as well. However, this could be asynchronous feedback with faculty providing feedback on notes submitted based on these encounters.

Overall, the senior 3rd year medical students noted the structured format, even remote, provided them with missing practice of key clinical skills such as history taking, clinical reasoning, counseling, and documentation. Students want more opportunities to practice, whether it be with residents as standardized patients or even potentially utilizing a peer system. One student noted “I don’t know how to practice the interview by myself!”

Of note, all ratings were student self-assessments pre- and post-course. This is a short-term measure and has obvious limitations. Therefore, future outcomes would include USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge and Clinical Skills scores and/or pass rates, faculty assessment of student performance in the small group sessions using structured grading rubrics, and formal grading of the TeleOSCE. In addition, data could be compared between a cohort completing this course and those who did not as a comparison to determine effectiveness.

Conclusion

Clinical skills with clinical reasoning at the foundation are essential for every future physician. In the COVID-19 pandemic, we know that students have had decreased clinical exposures and may continue to do so given changes in volume and a potential repeat surge. Thus, we must be creative and innovative in how we teach clinical skills, which at its core also needs to include clinical reasoning, practicing obtaining histories, identifying appropriate physical exam skills, developing differential diagnoses, counseling patients, and documenting in a patient note. This can be accomplished remotely through a structured clinical skills curriculum. Future curricula should consider peer to peer OSCE practice sessions, expansion to pre-clerkship years, and expanded faculty feedback on development of individualized learning plans, as well as objective outcome assessments including faculty assessments and/or USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge and/or Clinical Skills scores and pass rates.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AAMC:

-

American Association of Medical Colleges

- EPAs:

-

Entrustable Professional Activities

- OSCE:

-

Objective Structured Clinical Examination

- USMLE:

-

United States Medical Licensing Exam

References

The Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for entering residency. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas/publications. Published 2014. Accessed July 4, 2020.

Rencic J, Trowbridge RL Jr, Fagan M, Szauter K, Durning S. Clinical reasoning education at US medical schools: results from a national survey of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(11):1242–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4159-y.

van Gessel E, Nendaz MR, Vermeulen B, Junod A, Vu NV. Development of clinical reasoning from the basic sciences to the clerkships: a longitudinal assessment of medical students’ needs and self-perception after a transitional learning unit. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):966–74. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01672.x.

Durning SJ, LaRochelle J, Pangaro L, Artino AR Jr, Boulet J, van der Vleuten C, et al. Does the authenticity of preclinical teaching format affect subsequent clinical clerkship outcomes? A prospective randomized crossover trial. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24(2):177–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2012.664991.

Felix T, Richard D, Faber F, Zimmermann J, Adams N. Coffee talks: an innovative approach to teaching clinical reasoning and information mastery to medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10004.

Weinstein A, Pinto-Powell R. Introductory clinical reasoning curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10370. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10370.

Levin M, Cennimo D, Chen S, Lamba S. Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students: a case-based illness script worksheet approach. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10445. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10445.

Duca NS, Glod S. Bridging the gap between the classroom and the clerkship: a clinical reasoning curriculum for third-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10800. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10800.

Posel N, McGee JB, Fleiszer DM. Twelve tips to support the development of clinical reasoning skills using virtual patient cases. Med Teach. 2015;37(9):813–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.993951.

Palmer R, Biagioli FE, Mujcic J, Schneider BN, Spires L, Dodson L. The feasibility and acceptability of administering a telemedicine objective structured clinical exam as a solution for providing equivalent education to remote and rural learners. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3399 Available: www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/3399.

Cantone RE, Palmer R, Dodson LG, Biagioli FE. Insomnia telemedicine OSCE (TeleOSCE): a simulated standardized patient video-visit case for clerkship students. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10867. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10867.

Lara S, Foster CW, Hawks M, Montgomery M. Remote assessment of clinical skills during COVID-19: a virtual, high-stakes, summative pediatric objective structured clinical examination. Acad Pediatr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.05.029.

Stillman PL, Sabers DL, Redfield DL. The use of paraprofessionals to teach interviewing skills. Pediatrics. 1976;57(5):769–74.

ten Cate O. Introduction. In: ten Cate O, Custers E, Durning SJ, editors. Principles and practice of case-based clinical reasoning education: a method for preclinical students. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64828-6.

McBee E, Ratcliffe T, Schuwirth L, O’Neill D, Meyer H, Madden SJ, et al. Context and clinical reasoning. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7:256–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0417-x.

Funding

There was no external funding for this study. The study was supported by the Office of Education at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Traba drafted the initial manuscript. Drs. Holland, Laboy, Lamba, and Chen all reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Code availability

N/A

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Traba, C., Holland, B., Laboy, M.C. et al. A Multi-Modal Remote Clinical Skills Mini-Course Utilizing a Teaching TeleOSCE. Med.Sci.Educ. 31, 503–509 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01201-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01201-x