Abstract

Background

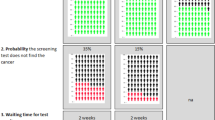

Evidence from discrete choice experiments can be used to enrich understanding of preferences, inform the (re)design of screening programmes and/or improve communication within public campaigns about the benefits and harms of screening. However, reviews of screening discrete choice experiments highlight significant discrepancies between stated choices and real choices, particularly regarding willingness to undergo cancer screening. The identification and selection of attributes and associated levels is a fundamental component of designing a discrete choice experiment. Misspecification or misinterpretation of attributes may lead to non-compensatory behaviours, attribute non-attendance and responses that lack external validity.

Objectives

We aimed to synthesise evidence on attribute development, alongside an in-depth review of included attributes and methodological challenges, to provide a resource for researchers undertaking future studies in cancer screening.

Methods

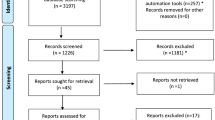

A systematic review was conducted to identify discrete choice experiments estimating preferences towards cancer screening, dated between 1990 and December 2020. Data were synthesised narratively. In-depth analysis of attributes led to classification into four categories: test specific, service delivery, outcomes and monetary. Attribute significance and relative importance were also analysed. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research conjoint analysis checklist was used to assess the quality of reporting.

Results

Forty-nine studies were included at full text. They covered a range of cancer sites: over half (26/49) examined colorectal screening. Most studies elicited general public preferences (34/49). In total, 280 attributes were included, 90% (252/280) of which were significant. Overall, test sensitivity and mortality reduction were most frequently found to be the most important to respondents.

Conclusions

Improvements in reporting the identification, selection and construction of attributes used within cancer screening discrete choice experiments are needed. This review also highlights the importance of considering the complexity of choice tasks when considering risk information or compound attributes. Patient and public involvement and stakeholder engagement are recommended to optimise understanding of unavoidably complex choice tasks throughout the design process. To ensure quality and maximise comparability across studies, further research is needed to develop a risk-of-bias measure for discrete choice experiments.

adapted from Moher, et al.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

12 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00562-8

References

Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Warren R. Screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):35.

Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, Rutter CM, Webber EM, O’Connor E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576–94.

Hirst Y, Stoffel S, Baio G, McGregor L, von Wagner C. Uptake of the English Bowel (colorectal) cancer screening programme: an update 5 years after the full roll-out. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:267–73.

Shahidi N, Cheung WY. Colorectal cancer screening: opportunities to improve uptake, outcomes, and disparities. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8(20):733–40.

NHS Digital. Cervical screening programme England 2017–18. 2018.

Moons L, Mariman A, Vermeir P, Colemont L, Clays E, Van Vlierberghe H, et al. Sociodemographic factors and strategies in colorectal cancer screening: a narrative review and practical recommendations. Acta Clin Belg. 2020;75(1):33–41.

Petkeviciene J, Ivanauskiene R, Klumbiene J. Sociodemographic and lifestyle determinants of non-attendance for cervical cancer screening in Lithuania, 2006–2014. Public Health. 2018;156:79–86.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7.

Vass CM, Payne K. Using discrete choice experiments to inform the benefit-risk assessment of medicines: are we ready yet? Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):859–66.

Ran T, Cheng C-Y, Misselwitz B, Brenner H, Ubels J, Schlander M. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening strategies: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(10):1969-81.e15.

Soekhai V, de Bekker-Grob EW, Ellis AR, Vass CM. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):201–26.

Ali S, Ronaldson S. Ordinal preference elicitation methods in health economics and health services research: using discrete choice experiments and ranking methods. Br Med Bull. 2012;103(1):21–44.

Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2(1):55–64.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health: a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, et al. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice development experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41.

Ghanouni A, Smith SG, Halligan S, Plumb A, Boone D, Yao GL, et al. Public preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests: a review of conjoint analysis studies. Expert Rev Med Dev. 2013;10(4):489–99.

Marshall D, McGregor SE, Currie G. Measuring preferences for colorectal cancer screening: what are the implications for moving forward? Patient. 2010;3(2):79–89.

Phillips KA, Van Bebber S, Marshall D, Walsh J, Thabane L. A review of studies examining stated preferences for cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A75.

Wortley S, Wong G, Kieu A, Howard K. Assessing stated preferences for colorectal cancer screening: a critical systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2014;7(3):271–82.

Mansfield C, Tangka FK, Ekwueme DU, Smith JL, Guy Jr GP, Li C, et al. Peer reviewed: stated preference for cancer screening: a systematic review of the literature, 1990–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Brouwer WB, Culyer AJ, van Exel NJA, Rutten FF. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):325–38.

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, van den Bos GA, Koopmanschap MA. Process utility from providing informal care: the benefit of caring. Health Policy. 2005;74(1):85–99.

Bien DR, Danner M, Vennedey V, Civello D, Evers SM, Hiligsmann M. Patients’ preferences for outcome, process and cost attributes in cancer treatment: a systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Patient. 2017;10(5):553–65.

Coast J, Smith RD, Lorgelly P. Welfarism, extra-welfarism and capability: the spread of ideas in health economics. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1190–8.

Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Prior T, Marshall DA, Cunningham C, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15.

Salkeld G, Ryan M, Short L. The veil of experience: do consumers prefer what they know best? Health Econ. 2000;9(3):267–70.

Gerard K, Shanahan M, Louviere J. Using stated preference discrete choice modelling to inform health care decisionmaking: a pilot study of breast screening participation. Appl Econ. 2003;35(9):1073–85.

Salkeld G, Solomon M, Short L, Ryan M, Ward JE. Evidence-based consumer choice: a case study in colorectal cancer screening. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27(4):449–55.

Fiebig DG, Haas M, Hossain I, Street DJ, Viney R. Decisions about Pap tests: what influences women and providers? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1766–74.

Howard K, Salkeld G. Does attribute framing in discrete choice experiments influence willingness to pay? Results from a discrete choice experiment in screening for colorectal cancer. Value Health. 2009;12(2):354–63.

Johar M, Fiebig DG, Haas M, Viney R. Using repeated choice experiments to evaluate the impact of policy changes on cervical screening. Appl Econ. 2013;45(14):1845–55.

Pignone MP, Howard K, Brenner AT, Crutchfield TM, Hawley ST, Lewis CL, et al. Comparing 3 techniques for eliciting patient values for decision making about prostate-specific antigen screening: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):362–8.

Brenner A, Howard K, Lewis C, Sheridan S, Crutchfield T, Hawley S, et al. Comparing 3 values clarification methods for colorectal cancer screening decision-making: a randomized trial in the US and Australia. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(3):507–13.

Howard K, Salkeld GP, Patel MI, Mann GJ, Pignone MP. Men’s preferences and trade-offs for prostate cancer screening: a discrete choice experiment. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):3123–35.

Spinks J, Janda M, Soyer HP, Whitty JA. Consumer preferences for teledermoscopy screening to detect melanoma early. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22(1):39–46.

Osborne JM, Flight I, Wilson CJ, Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Young GP. The impact of sample type and procedural attributes on relative acceptability of different colorectal cancer screening regimens. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1825–36.

Snoswell CL, Whitty JA, Caffery LJ, Loescher LJ, Gillespie N, Janda M. Direct-to-consumer mobile teledermoscopy for skin cancer screening: preliminary results demonstrating willingness-to-pay in Australia. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(10):683–9.

Marshall DA, Johnson R, Kulin NA, Ozdemir A, Walsh A, Marshall J, et al. How do physician assessments of patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests differ from actual preferences? A comparison in Canada and the United States using a stated-choice survey. Health Econ. 2009;18(12):1420–39.

Pignone MP, Brenner AT, Hawley S, Sheridan SL, Lewis CL, Jonas DE, et al. Conjoint analysis versus rating and ranking for values elicitation and clarification in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):45–50.

Pignone MP, Crutchfield TM, Brown PM, Hawley ST, Laping JL, Lewis CL, et al. Using a discrete choice experiment to inform the design of programs to promote colon cancer screening for vulnerable populations in North Carolina. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:611.

Kistler CE, Hess TM, Howard K, Pignone MP, Crutchfield TM, Hawley ST, et al. Older adults’ preferences for colorectal cancer-screening test attributes and test choice. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1005–16.

Martens CE, Crutchfield TM, Laping JL, Perreras L, Reuland DS, Cubillos L, et al. Why wait until our community gets cancer? Exploring CRC screening barriers and facilitators in the Spanish-speaking community in North Carolina. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(4):652–9.

Mansfield C, Ekwueme DU, Tangka FKL, Brown DS, Smith JL, Guy GP, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: preferences, past behavior, and future intentions. Patient. 2018;11(6):599–611.

Hendrix N, Hauber B, Lee CI, Bansal A, Veenstra DL. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer screening: primary care provider preferences. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(6):1117–242.

Hol L, De Bekker-Grob EW, Van Dam L, Donkers B, Kuipers EJ, Habbema JDF, et al. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening strategies: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(6):972–80.

van Dam L, Hol L, Bekker-Grob EWD, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Habbema JDF, et al. What determines individuals’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening programmes? A discrete choice experiment. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(1):150–9.

de Bekker-Grob E, Rose JM, Donkers B, Essink-Bot ML, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW. Men’s preferences for prostate cancer screening: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(3):533–41.

Benning TM, Dellaert BGC, Dirksen CD, Severens JL. Preferences for potential innovations in non-invasive colorectal cancer screening: a labeled discrete choice experiment for a Dutch screening campaign. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(7):898–908.

Benning TM, Dellaert BGC, Severens JL, Dirksen CD. The effect of presenting information about invasive follow-up testing on individuals’ noninvasive colorectal cancer screening participation decision: results from a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2014;17(5):578–87.

Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, Fermont JM, van Til JA, Ijzerman MJ. Public stated preferences and predicted uptake for genome-based colorectal cancer screening. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:18.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Veldwijk J, Jonker MF, Buis S, Huisman J, et al. What factors influence non-participation most in colorectal cancer screening? A discrete choice experiment. Patient. 2021;14(2):269–81.

Peters Y, Siersema PD. Public preferences and predicted uptake for esophageal cancer screening strategies: a labeled discrete choice experiment. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11(11):e00260.

Ryan M, Wordsworth S. Sensitivity of willingness to pay estimates to the level of attributes in discrete choice experiments. Scottish J Political Econ. 2000;47(5):504–24.

Boone D, Mallett S, Zhu S, Yao GL, Bell N, Ghanouni A, et al. Patients’ & healthcare professionals’ values regarding true- & false-positive diagnosis when colorectal cancer screening by CT colonography: discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e80767.

Ghanouni A, Halligan S, Taylor SA, Boone D, Plumb A, Stoffel S, et al. Quantifying public preferences for different bowel preparation options prior to screening CT colonography: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004327.

Plumb AA, Boone D, Fitzke H, Helbren E, Mallett S, Zhu S, et al. Detection of extracolonic pathologic findings with CT colonography: a discrete choice experiment of perceived benefits versus harms. Radiology. 2014;273(1):144–52.

Kitchener HC, Gittins M, Rivero-Arias O, Tsiachristas A, Cruickshank M, Gray A, et al. A cluster randomised trial of strategies to increase cervical screening uptake at first invitation (STRATEGIC). Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(68):1–138.

Vass CM, Rigby D, Payne K. Investigating the heterogeneity in women’s preferences for breast screening: does the communication of risk matter? Value Health. 2018;21(2):219–28.

Berchi C, Dupuis J-M, Launoy G. The reasons of general practitioners for promoting colorectal cancer mass screening in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7(2):91–8.

Nayaradou M, Berchi C, Dejardin O, Launoy G. Eliciting population preferences for mass colorectal cancer screening organization. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):224–33.

Sicsic J, Krucien N, Franc C. What are GPs’ preferences for financial and non-financial incentives in cancer screening? Evidence for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. Soc Sci Med. 2016;167:116–27.

Papin-Lefebvre F, Guillaume E, Moutel G, Launoy G, Berchi C. General practitioners’ preferences with regard to colorectal cancer screening organisation colon cancer screening medico-legal aspects. Health Policy. 2017;121(10):1079–84.

Sicsic J, Pelletier-Fleury N, Moumjid N. Women’s benefits and harms trade-offs in breast cancer screening: results from a discrete-choice experiment. Value Health. 2018;21(1):78–88.

Charvin M, Launoy G, Berchi C. The effect of information on prostate cancer screening decision process: a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10.

Raginel T, Grandazzi G, Launoy G, Trocmé M, Christophe V, Berchi C, et al. Social inequalities in cervical cancer screening: a discrete choice experiment among French general practitioners and gynaecologists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Arana JE, Leon CJ, Quevedo JL. The effect of medical experience on the economic evaluation of health policies: a discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(2):512–24.

Chamot E, Mulambia C, Kapambwe S, Shrestha S, Parham GP, Macwan’gi M, et al. Preference for human papillomavirus-based cervical cancer screening: results of a choice-based conjoint study in Zambia. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. 2015;19(2):119–23.

Li S, Liu S, Ratcliffe J, Gray A, Chen G. Preferences for cervical cancer screening service attributes in rural China: a discrete choice experiment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:881.

Oberlin AM, Pasipamire T, Chibwesha CJ. Exploring women’s preferences for HPV-based cervical cancer screening in South Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;146(2):192–9.

Bilger M, Özdemir S, Finkelstein EA. Demand for cancer screening services: results from randomized controlled discrete choice experiments. Value Health. 2020;23(9):1246–55.

Kohler RE, Gopal S, Lee CN, Weiner BJ, Reeve BB, Wheeler SB. Breast cancer knowledge, behaviors, and preferences in Malawi: implications for early detection interventions from a discrete choice experiment. J Global Oncol. 2017;3(5):480–9.

Mandrik O, Yaumenenka A, Herrero R, Jonker MF. Population preferences for breast cancer screening policies: discrete choice experiment in Belarus. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0224667.

Light A, Elhage O, Marconi L, Dasgupta P. Prostate cancer screening: where are we now? BJU Int. 2019;123(6):916–7.

Ramezani Doroh V, Delavari A, Yaseri M, Sefiddashti SE, Akbarisari A. Preferences of Iranian average risk population for colorectal cancer screening tests. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2019;32(4):677–87.

Marshall DA, Johnson FR, Phillips KA, Marshall JK, Thabane L, Kulin NA. Measuring patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening using a choice-format survey. Value Health. 2007;10(5):415–30.

Mühlbacher A, Bethge S, Sadler A. Compound attributes for side effect in discrete choice experiments: risk or severity: what is more important to hepatitis C patients? Value Health. 2015;18(7):A629–30.

Harrison M, Rigby D, Vass C, Flynn T, Louviere J, Payne K. Risk as an attribute in discrete choice experiments: a systematic review of the literature. Patient. 2014;7(2):151–70.

Freeman AM, Herriges JA, Kling CL. The measurement of environmental and resource values: theory and methods. New York: Routledge; 2014.

Spinks J, Mortimer D. Lost in the crowd? Using eye-tracking to investigate the effect of complexity on attribute non-attendance in discrete choice experiments. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;16:14.

Regier DA, Watson V, Burnett H, Ungar WJ. Task complexity and response certainty in discrete choice experiments: an application to drug treatments for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Behav Exp Econ. 2014;50:40–9.

Flynn TN, Bilger M, Malhotra C, Finkelstein EA. Are efficient designs used in discrete choice experiments too difficult for some respondents? A case study eliciting preferences for end-of-life care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(3):273–84.

Jonker MF, Donkers B, de Bekker-Grob E, Stolk EA. Attribute level overlap (and color coding) can reduce task complexity, improve choice consistency, and decrease the dropout rate in discrete choice experiments. Health Econ. 2019;28(3):350–63.

Veldwijk J, Determann D, Lambooij MS, Van Til JA, Korfage IJ, de Bekker-Grob EW, et al. Exploring how individuals complete the choice tasks in a discrete choice experiment: an interview study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:45.

Ericsson KA, Simon HA. How to study thinking in everyday life: contrasting think-aloud protocols with descriptions and explanations of thinking. Mind Cult Activ. 1998;5(3):178–86.

Aguiar M, Harrison M, Munro S, Burch T, Kaal KJ, Hudson M, et al. Designing discrete choice experiments using a patient-oriented approach. Patient. 2021;14(4):389–97.

Barber S, Bekker H, Marti J, Pavitt S, Khambay B, Meads D. Development of a discrete-choice experiment (DCE) to elicit adolescent and parent preferences for hypodontia treatment. Patient. 2019;12(1):137–48.

McCarthy MC, De Abreu LR, McMillan LJ, Meshcheriakova E, Cao A, Gillam L. Finding out what matters in decision-making related to genomics and personalized medicine in pediatric oncology: developing attributes to include in a discrete choice experiment. Patient. 2020;13(3):347–61.

Sarikhani Y, Ostovar T, Rossi-Fedele G, Edirippulige S, Bastani P. A protocol for developing a discrete choice experiment to elicit preferences of general practitioners for the choice of specialty. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;25:80–9.

Vellinga A, Devine C, Ho MY, Clarke C, Leahy P, Bourke J, et al. What do patients value as incentives for participation in clinical trials? A pilot discrete choice experiment. Res Ethics. 2020;16(1–2):1–12.

Hollin IL, Craig BM, Coast J, Beusterien K, Vass C, DiSantostefano R, et al. Reporting formative qualitative research to support the development of quantitative preference study protocols and corresponding survey instruments: guidelines for authors and reviewers. Patient. 2020;13(1):121–36.

Shields GE, Brown L, Wells A, Capobianco L, Vass C. Utilising patient and public involvement in stated preference research in health: learning from the existing literature and a case study. Patient. 2021;14(4):399–412.

Hawton A, Boddy K, Kandiyali R, Tatnell L, Gibson A, Goodwin E. Involving patients in health economics research: “the PACTS principles.” Patient. 2021;14(4):429–34.

Callender T, Emberton M, Morris S, Pharoah PD, Pashayan N. Benefit, harm, and cost-effectiveness associated with magnetic resonance imaging before biopsy in age-based and risk-stratified screening for prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e2037657.

Griffin E, Hyde C, Long L, Varley-Campbell J, Coelho H, Robinson S, et al. Lung cancer screening by low-dose computed tomography: a cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative programmes in the UK using a newly developed natural history-based economic model. Diagn Progn Res. 2020;4(1):1–11.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Pollard K, Donskoy A-L, Moule P, Donald C, Lima M, Rice C. Developing and evaluating guidelines for patient and public involvement (PPI) in research. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015;28(2):141–55.

Edwards AG, Naik G, Ahmed H, Elwyn GJ, Pickles T, Hood K, et al. Personalised risk communication for informed decision making about taking screening tests. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD001865.

Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA. Helping patients decide: ten steps to better risk communication. J Nat Cancer Instit. 2011;103(19):1436–43.

Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327(7417):745–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jenny Lowe, University of Exeter for helping to run the database searches that formed part of this review. We thank Nia Morrish for assisting in the initial screening of the search results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research arises from the CanTest Collaborative, which is funded by Cancer Research UK (reference number: C8640/A23385), of which Rebekah Hall is a funded PhD student, Willie Hamilton is a director and Anne E. Spencer is a senior faculty member.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Searches, screening and data abstraction were performed by RH and AM-L. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

The original Online version of this article was revised: The data points In figure 2 were missed and published.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, R., Medina-Lara, A., Hamilton, W. et al. Attributes Used for Cancer Screening Discrete Choice Experiments: A Systematic Review. Patient 15, 269–285 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00559-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00559-3