Abstract

Background

Burnout among primary care physicians, advanced practice clinicians (nurse practitioners and physician assistants [APCs]), and staff is common and associated with negative consequences for patient care, but the association of burnout with characteristics of primary care practices is unknown.

Objective

To examine the association between physician-, APC- and staff-reported burnout and specific structural, organizational, and contextual characteristics of smaller primary care practices.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of survey data collected from 9/22/2015–6/19/2017.

Setting

Sample of smaller primary care practices in the USA participating in a national initiative focused on improving the delivery of cardiovascular preventive services.

Participants

10,284 physicians, APCs and staff from 1380 primary care practices.

Main Measure

Burnout was assessed with a validated single-item measure.

Key Results

Burnout was reported by 20.4% of respondents overall. In a multivariable analysis, burnout was slightly more common among physicians and APCs (physician vs. non-clinical staff, adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.49, APC vs. non-clinical staff, aOR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.10–1.62). Other multivariable correlates of burnout included non-solo practice (2–5 physician/APCs vs. solo practice, aOR = 1.71; 95% CI, 1.35–2.16), health system affiliation (vs. physician/APC-owned practice, aOR = 1.42; 95%CI, 1.16–1.73), and Federally Qualified Health Center status (vs. physician/APC-owned practice, aOR = 1.36; 95%CI, 1.03–1.78). Neither the proportion of patients on Medicare or Medicaid, nor practice-level patient volume (patient visits per physician/APC per day) were significantly associated with burnout. In analyses stratified by professional category, practice size was not associated with burnout for APCs, and participation in an accountable care organization was associated with burnout for clinical and non-clinical staff.

Conclusions

Burnout is prevalent among physicians, APCs, and staff in smaller primary care practices. Members of solo practices less commonly report burnout, while members of health system-owned practices and Federally Qualified Health Centers more commonly report burnout, suggesting that practice level autonomy may be a critical determinant of burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Burnout, a psychological state characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a perceived lack of effectiveness,1 is common and, by some accounts, worsening in primary care.2,3,4,5,6 Although absolute levels of burnout vary depending on the measure used,7 current evidence suggests burnout may be related to the changing environment of care including increased workload,8, 9 clerical task performance,7 use of electronic health records (EHR),10,11,12 engagement in practice change initiatives,13 and the rising complexity of primary care practice.14 The potential consequences are serious for patients, clinicians, and staff, as burnout is associated with poorer care quality,8, 15 lower patient satisfaction,16, 17 decreased patient safety,18 employee work-hour reductions,19, 20 and turnover.21 While many recent studies of burnout in health care have focused on physicians, primary care is increasingly delivered by multidisciplinary teams.22 Other studies have focused on large health systems9, 23 and have included relatively few physicians, advanced practice clinicians (nurse practitioners, physician assistants [APCs]), and staff from small, independent primary care practices.24, 25

Little is known about how structural, organizational, and contextual characteristics relate to burnout in smaller practices, where over 75% of Americans receive primary care,26 or whether non-physician team members also suffer from burnout. Therefore, we examined the prevalence of burnout among physicians, APCs and staff, and the relationship between practice-level organizational characteristics and burnout in a large national sample of smaller primary care practices, with the aim of identifying practice characteristics and environments that may provide protection or risk for burnout. Findings from this study may inform policy efforts designed to support clinical teams in smaller primary care practices.

METHODS

Setting

In 2015, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) launched EvidenceNOW, a nationwide initiative to promote evidence-based cardiovascular preventive care in smaller primary practices. The seven regional EvidenceNOW cooperatives worked with 1716 practices in 12 US states, in which over 5000 physician and APCs care for over 8 million patients. AHRQ additionally funded an independent national evaluation of these seven cooperatives, “Evaluating System Change to Advance Learning and Take Evidence to Scale (ESCALATES),”27 which aggregated the data used in this study.

Participants and Procedures

Each EvidenceNOW cooperative aimed to enroll at least 200 smaller primary care practices, defined as practices with up to ten physicians/APCs.27 Because of recruitment challenges, the funder allowed some cooperatives to recruit a few practices with up to 15 full-time clinicians. Practices were included if they used an EHR and if they had little or no internal quality improvement support.

Surveys were fielded by EvidenceNOW cooperatives prior to practice interventions, 9/22/2015–06/19/2017. Cooperatives administered a Practice Survey to a self-identified practice leader (e.g., office manager, lead physician/APC), collecting information on practice structure. Cooperatives also administered a Practice Member Survey to all members of each practice. The sample frame of practices was all those participating in EvidenceNOW, while the sample frame of practice members was all practice members in participating practices at the time of survey administration. Cooperatives selected the mode in which the survey was administered (paper, web-based, phone) to suit their practices’ needs. Incentives were offered by most cooperatives to practices and practice members for survey completion. Incentives varied in size ($2–$75) and type (cash, gift card) per cooperative. EvidenceNOW cooperatives were instructed to ensure respondent confidentiality during survey administration.

Practice survey response rate was calculated as the number of participating practices that completed a practice survey. Practice member survey response rate was calculated as the number of surveys returned divided by the number of practice members in each practice at the time of survey administration. For 153 practices (~ 11%), we had incomplete response rate data; we used a multiple imputation approach to estimate response rate based on the number of surveys returned, and responses reported in the practice survey (see Online Appendix Table 1 for details).

Survey Measures

At study initiation, EvidenceNOW cooperatives and the ESCALATES team collaboratively developed a core set of survey measures. The Practice Survey collected structural characteristics, such as practice size, ownership, staffing, EHR capabilities, registry use, recent practice disruptions (e.g., employee turnover, EHR implementation), participation in accountable care organizations (ACOs), and participation in other practice-change initiatives (e.g., State Innovation Models initiative, Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative). Additional questions included proportion of patients with Medicare or Medicaid, and average patient volume (patient visits per physician/APC per day). The practice member survey included questions on the primary outcome of burnout and other individual member characteristics, including professional category [i.e., physician, APC, clinical staff (e.g. registered nurse, medical assistant, behavioral health provider), non-clinical staff (e.g. receptionist, billing staff) and other], length of employment, and hours worked per week. Burnout was measured by a single-item, 5-point measure validated against the emotional exhaustion scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI),28, 29 and which has been used in multiple studies5, 7,8,9, 23, 30—“Overall, based on your definition of burnout, how would you rate your level of burnout?” Responses were scored on a five-category ordinal scale:

-

1 = I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout.

-

2 = Occasionally, I am under stress, and I do not always have as much energy as I once did, but I do not feel burned out.

-

3 = I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion.

-

4 = The symptoms of burnout that I am experiencing will not go away. I think about frustration at work a lot.

-

5 = I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help.

As defined in prior work, a person reporting a score of 3 or higher was considered to be experiencing burnout.23 A complete list of survey items is found in Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

We used summary statistics (counts and proportions) to describe characteristics of the EvidenceNOW practices, the practice-member respondents involved in the study, and the prevalence of burnout by member role and practice characteristics. To determine the member- and practice-level factors associated with burnout, we performed multivariable member-level generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression models of burnout (dichotomized as yes/no) with robust sandwich variance estimators that accounted for clustering of members within a practice (assuming an exchangeable correlation structure) as a function of selected practice organizational and individual characteristics (Table 2). We performed analyses for the entire sample, and stratified by professional category. We used multiple imputation by chained equations to account for missing data in member- and practice-level characteristics.31 Final estimated odds ratio of burnout and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals across 50 imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules.

As a sensitivity analysis, we performed univariable models and multivariable models of burnout as a function of member and practice characteristics, including dummy variables for missing covariate responses, to avoid removing members from the analyses and maintain the overall sample. For all models, we excluded 617 (5.6%) members that did not respond to the burnout item. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.0 and statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University and was registered as an observational study at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02560428).

RESULTS

Of 1716 enrolled practices, 1492 returned practice surveys (87% response rate), and 1501 returned at least one practice member survey (88% response rate). Among 1380 practices that submitted a practice survey and had at least one practice member respondent (80% of enrolled practices), 10,901 practice members responded (with 10,284 responses to the burnout item), a mean of 7.9 respondents per practice, with an estimated per-practice response rate of 75.8% (see Online Appendix Table 1 for details).

Practice and practice-member characteristics are presented in Table 1. Almost 15% of respondents were physicians, 9.2% were APCs, 35.6% were clinical staff, 21.7% were non-clinical staff, and 6.4% were office managers. Forty-five percent had worked in their current practice for over 3 years, and 15.3% worked more than 40 hours per week.

Just under one-quarter of practices were solo practices, and nearly half had 2–5 physicians/APCs. Nearly 40% of practices were physician/APC-owned, just over 20% were owned by hospitals or health systems, and 16.4% were Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs). Sixteen percent of practices were located in rural areas, and 32.3% were in a medically underserved area. Nearly 40% reported patient-centered medical home (PCMH) recognition, and 30% reported participating in other demonstration projects. Nearly 40% reported participating in an ACO, and just over half reported receiving incentives or payments based on clinical quality, adoption/use of information technology, or patient satisfaction.

Sixty-two percent of practices reported using registries, and 71.6% of practices acknowledged participating in Meaningful Use32; almost 20% reported experiencing multiple practice disruptions in the prior 12 months. Practice characteristics were similar between practices with and without responses to the burnout survey item (Online Appendix Table 2).

Burnout

Burnout was present in 20.4% of respondents overall, ranging from 25.1% of physicians to 17.2% of office managers (multivariable analysis in Table 2 and Online Appendix Table 4). In multivariable models, the odds of burnout were higher among non-solo practices as compared to solo practices (e.g., 2–5 physician/APCs vs. solo practice, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.35–2.16). People who worked in hospital- or health system-owned practices and FQHCs had higher odds of burnout than people working in physician/APC-owned practices (hospital/health system: aOR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.16–1.73; FQHC: aOR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.03–1.78). There was no significant difference in burnout by practice location.

Practice members whose practice reported participating in an ACO had higher odds of burnout (aOR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.08–1.48). Neither the proportion of patients covered by Medicare or Medicaid, nor practice level patient volume (patient visits per physician/APC per day) was associated with practice member burnout.

Physician and APCs had higher odds of burnout than non-clinical staff (physician vs. non-clinical staff, aOR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.05–1.49, nurse practitioner or physician assistant vs. non-clinical staff, aOR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.10–1.62). Individuals who worked more than 3 years in their current practice, and worked more than 40 h per week had higher odds of reporting burnout.

The sensitivity analyses using missing data indicators in univariable and multivariable GEE models to examine the potential bias related to missing practice and practice member characteristics data (Online Appendix Tables 3 and 4) demonstrated similar findings to the multiply-imputed multivariable GEE models.

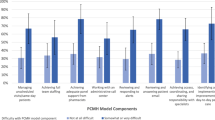

In analyses stratified by professional category (Fig. 1), practice size was not associated with burnout for APCs (e.g., 11+ clinicians vs. solo, aOR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.35–2.07), but the effect size on burnout among physicians was larger than in the overall practice member model (e.g., 11+ clinicians vs. solo, aOR = 3.60, 95% CI 2.03–6.34 in stratified analysis vs. aOR = 2.01, 95% CI 1.52–2.65 in overall practice member model). Practice ownership was not associated with burnout among non-clinical staff, and practice participation in an ACO was associated with burnout, but only for clinical and non-clinical staff. Full stratified model results are presented in Online Appendix Table 5.

Adjusted odds of burnout by practice and practice member characteristics overall and stratified by member role in practice. HS, health system; FQHC, Federally Qualified Health Center; ACO, accountable care organization; WK, week; MD, doctor of medicine; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant. Only the significant practice and practice member characteristics in the overall sample are displayed. For all characteristics, please refer to supplementary materials. Statistical significance is denoted by the asterisk (p < 0.05)

DISCUSSION

This national study of burnout in over 10,000 members of over 1300 smaller primary care practices has several notable findings. First, while physicians and APCs had slightly higher levels of burnout, burnout was prevalent among all employee types. Second, members of solo practices reported less burnout compared to larger practices. Third, people working in physician- or APC-owned practices reported less burnout compared to those working in health system-owned practices and FQHCs. Finally, patient volume at the practice level was not associated with burnout.

Much recent attention to burnout in health care has been focused on physicians; in this work, we demonstrate that nurse practitioners and physician assistants in primary care experience burnout at similar levels. Additionally, burnout was more common among clinical staff than non-clinical staff. However, burnout was prevalent among all roles in the practice, suggesting it may be a characteristic of specific practices, or primary care in general. Practice characteristics were associated with burnout, suggesting that organization-level factors may be important drivers of burnout. Indeed, recent systematic reviews show that initiatives targeting organizations, not only individual employees, are critical to reduce burnout.33, 34

Primary care is physically, emotionally, and cognitively demanding work.35 Consistent with prior studies, we found that working more hours per week, as reported by practice members, is associated with more burnout. Our findings complement research on primary care burnout conducted in larger practice settings. Helfrich, et al. demonstrated that in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, primary care workload, as measured by panel overcapacity, was strongly associated with burnout.9 Yet, recent evidence, including findings from this study, suggest that number of hours worked by itself may not be directly related to burnout.36 Factors such as perceived control over work, autonomy, relatedness, competence, and values congruence may be important factors influencing burnout in large and small practices.37

Social determination theory (SDT) suggests that three innate psychological needs drive human well-being: autonomy, relatedness, and competence, and—when fulfilled—people express vitality, curiosity, and self-motivation. When these needs are unmet, people become apathetic, alienated, and diminished.38 Our findings align with SDT and an emerging literature, suggesting that practice features related to autonomy, relatedness, and competence (e.g., solo practice, clinician ownership) are protective for burnout.39,40,41,42 People working in solo and clinician-owned practices may have more autonomy and decision-making power than those working in system-owned practices,43 and may also have a higher sense of relatedness, with fewer employees, closer working relationships, and a shared sense responsibility for the practice’s success. In contrast, external measurement and reward systems, as are frequently used in health systems and FQHCs, may erode clinician and staff perceptions of competence and autonomy,44 and undermine intrinsic motivation, leading to burnout.45

Burnout also may be attributable to the type and difficulty of work. For example, we observed that burnout was associated with working in FQHC practices, where practice staff manage large, complex and vulnerable patient panels, and may lack critical resources. This finding aligns with observations of larger FQHCs, where Friedberg, et al. found that burnout was increasing over time, while perceived control of work was decreasing.6 We also observed that other workload-related practice characteristics, such as the approximate proportion of patients on Medicare or Medicaid, practice location in a medically underserved area, and patient volume, were not associated with burnout. This suggests that the additional workload associated with these variables may not directly impact burnout, but these variables might interact with other unmeasured factors through indirect pathways.

Analyses stratified by professional category revealed important differences in the association of practice size and ownership with burnout. Practice size was not associated with burnout for APCs, while being associated with burnout for all other professional categories. It may be that in larger practice settings APCs may practice more independently and have greater autonomy, protecting them from burnout. Additionally, practice ownership had no relationship with burnout among non-clinical staff. This null finding may indicate various trends within practices. Non-clinical staff members may already lack autonomy, and the practice ownership does not impact their work life. Alternatively, outside ownership may provide staff with greater benefits and new opportunities for career advancement, while simultaneously reducing practice relatedness, leading to mixed impact on burnout.

Policy efforts to improve primary care often impose requirements on practices, such as the use of quality measures, or the adoption of specific practice structures or capabilities, such as EHRs. In our study, PCMH recognition and participation in other transformation initiatives were not associated with burnout, while participation in an ACO was (among clinical and non-clinical staff only). ACOs may encourage practices to makes changes in practice patterns and require reporting on specific quality measures, and much of this work may fall on staff members, leading to burnout.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, we cannot be certain about causation. Second, we use a single-item measure of self-defined burnout, whereas other survey measures of burnout, such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), separately measure three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and feelings of ineffectiveness. However, the single-item measure we used correlates with the emotional exhaustion subscale of the MBI,28, 29 has been used in multiple large studies8, 9, 23, 46 and has been adopted by the American Medical Association for burnout prevention efforts. Third, we relied on respondent self-reporting to determine practice characteristics, and in some practices respondents may not have had the necessary information to accurately complete the survey. However, we encouraged respondents to seek information from multiple sources to get the most accurate data. Fourth, as cooperatives did not collect data on response rate by professional category, we were unable to use non-response weights by professional category in our modeling approach. Finally, our sample consists of smaller primary care practices willing to engage in an external quality improvement project, and these practices may have differing levels of burnout than other practices. Nonetheless, our estimates of burnout prevalence are similar to other recent studies using similar measures.5, 7

CONCLUSION

Burnout is common among physicians, APCs and staff in smaller primary care practices. Burnout was less common among solo and physician- or APC-owned practices and was more common among health system practices and FQHCs. While solo and independently owned practices provide a large proportion of primary care,26 as policy and economic forces continue to promote consolidation and external ownership47, 48 increased burnout among practice members may be a consequence. Future efforts to promote improvement of primary care should consider strategies that minimize burnout risk. These may include programs and policies that support and strengthen solo and smaller practices and encourage distribution of leadership and decision-making at the practice level in system-owned practices—promoting agency, enhancing intrinsic motivation, and creating work environments that ensure team members feel valued, engaged, and perform personalized work. Importantly, programs and policies need to take into account the work environment and degree of autonomy afforded all practice members, not just physicians.

References

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205. Published September 17, 2007. Accessed 14 Aug 2018.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–85.

Simonetti JA, Sylling PW, Nelson K, et al. Patient-centered medical home implementation and burnout among VA primary care employees. J Ambul Care Manage. 2017;40(2):158–66.

Puffer JC, Knight C, O'Neill TR, et al. Prevalence of burnout in board certified family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(2):125–6.

Friedberg MW, Reid RO, Timbie JW, et al. Federally Qualified Health Center clinicians and staff increasingly dissatisfied with workplace conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1469–75.

Rassolian M, Peterson LE, Fang B, et al. Workplace factors associated with burnout of family physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1036–8.

Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28–36, W6–9.

Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–6.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–48.

Howard J, Clark EC, Friedman A, et al. Electronic health record impact on work burden in small, unaffiliated, community-based primary care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;28(1):107–13.

Gregory ME, Russo E, Singh H. Electronic health record alert-related workload as a predictor of burnout in primary care providers. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(3):686–97.

Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaén CR. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: lessons from the national demonstration project. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):439–45.

Katerndahl DA, Wood R, Jaén CR. A method for estimating relative complexity of ambulatory care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(4):341–7.

DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):93–102.

Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):122–8.

Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29–39.

West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1071–8.

Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional Satisfaction and the Career Plans of US Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:1625–35.

Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–31.

Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, Blumenthal D. Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care. 2006;44(3):234–42.

Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):272–8.

Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Simonetti J, et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 2:S659–66.

Cuellar A, Krist AH, Nichols LM, Kuzel AJ. Effect of Practice Ownership on Work Environment, Learning Culture, Psychologicl Safety, and Burnout. Ann Fam Med 2018;16:S44-S51.

Blechter B, Jiang N, Cleland C, Berry C, Ogedegbe O, Shelley D. Correlates of Burnout in Small Independent Primary Care Practices in an Urban Setting. J Am Board Fam Med 2018;31(4).

Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics and disparities among primary care practices in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):481–6.

Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Gordon L, et al. A national evaluation of a dissemination and implementation initiative to enhance primary care practice capacity and improve cardiovascular disease care: the ESCALATES study protocol. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):86.

Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–7.

Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–9.

Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, et al. Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):441–50.

White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–99.

US Department of Health and Human Services. 2015 Edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) Certification Criteria, 2015 Edition Base Electronic Health Record (EHR) Definition, and ONC Health IT Certification Program Modifications. 45 CFR §170. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2015-06612. Published March 30, 2015. Accessed 14 Aug 2018.

Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195–205.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–81.

Sinsky C, Tutty M, Colligan L. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):683–4.

Weidner AKH, Phillips RL Jr, Fang B, Peterson LE. Burnout and scope of practice in new family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):200–5.

Gregory ST, Menser T. Burnout among primary care physicians: a test of the areas of worklife model. J Healthc Manag. 2015;60(2):133–48.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78.

Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285–308. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2392498. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Portoghese I, Galletta M, Coppola RC, Finco G, Campagna M. Burnout and workload among health care workers: the moderating role of job control. Saf Health Work. 2014;5(3):152–7.

DeVoe J, Fryer Jr GE, Hargraves JL, Phillips RL, Green LA. Does career dissatisfaction affect the ability of family physicians to deliver high-quality patient care? J Fam Pract. 2002;51(3):223–8.

Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997-2001. JAMA. 2003;289(4):442–9.

Liaw WR, Jetty A, Petterson SM, Peterson LE, Bazemore AW. Solo and small practices: a vital, diverse part of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):8–15.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(6):627–68; discussion 692-700.

Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37(11):1140–54.

Peterson LE, Baxley E, Jaén CR, Phillips RL. Fewer family physicians are in solo practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(1):11–2.

Isaacs SL, Jellinek PS, Ray WL. The independent physician--going, going…. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(7):655–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the EvidenceNOW Cooperatives for their work on this initiative. We additionally wish to thank Alex Preston, Tanisha Tate-Woodson, Jennifer Hemler, Brianna Muller, and Amanda Delzer Hill for their contributions.

Funding

This research was supported by grant no. R01HS023940-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

Dr. Edwards and Dr. Ono are employees of the Unites States Department of Veterans Affairs. The ideas expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent any official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Additional information

Prior Presentations: We presented this work as a plenary at the National Society for General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Washington, DC, on April 20, 2017, and as an oral presentation at the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting in Montréal, Québec, November 19, 2017.

Registration: Evaluating System Change to Advance Learning and Take Evidence to Scale (ESCALATES) is registered as an observational study at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02560428).

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 84.4 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, S.T., Marino, M., Balasubramanian, B.A. et al. Burnout Among Physicians, Advanced Practice Clinicians and Staff in Smaller Primary Care Practices. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 2138–2146 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4679-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4679-0