Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of patients with intussusception, with special regard to the duration of symptoms, referral from other hospitals, outcome and complications related to delayed diagnosis.

Methods

This retrospective study was performed using hospital charts, ultrasound and radiological reports and surgical notes from patients treated in our institution from 1996–2005.

Results

Altogether 98 patients were included in the study. The study revealed idiopathic intussusception in 95% of the cases. The remaining patients presented with Meckel’s diverticulum and schwannoma of the small bowel. We used ultrasound as the primary modality for diagnosis in all the patients, with a diagnostic accuracy of 100% in our study. Conservative treatment using an air enema was successful in 79.5% of cases. A higher rate of surgical intervention was found in patients who had symptoms for more than 24 h and in referred patients.

Conclusions

Particular attention needs to be paid to the rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment of intussusception. Uncertain cases should be urgently referred to specialised paediatric centres. Ultrasound should be the diagnostic method of choice, since it is very effective in making this diagnosis. The first treatment option for intussusception remains the enema. Delayed diagnosis leads to an increased number of open surgeries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intussusception is one of the most frequent causes of bowel obstruction in infancy, leading to intestinal necrosis, bowel resection, and even death if not recognised and treated appropriately [1]. Intussusception seems to be idiopathic in 90% of cases and is rarely associated with pathological lead points such as Meckel’s diverticulum, solid bowel lesions and intestinal lymphoma [2]. Intussusception has also been reported to occur postoperatively and after blunt abdominal trauma [3, 4].

The diagnosis of intussusception is challenging due to a wide variety of clinical presentations and overlaps with other abdominal conditions [5–7]. It is assumed that the delayed diagnosis of intussusception increases the incidence of surgical treatment and the risk of complications.

This present study evaluated the outcome of patients with intussusception treated in our institution, with special regard to the cause of the lesion, diagnostic procedures, treatment methods and the duration of symptoms. Furthermore, we investigated whether the time of referral of patients with suspected intussusception has an impact on the rate of open surgery. This would lead to the recommendation of sending patients with suspected intussusception as early as possible to a tertiary care centre.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study was performed to evaluate patients with acute intussusception from 1996–2005 using hospital charts, ultrasound and radiological reports and surgical notes. Patients with acute intussusception were distinguished from chronic cases by the sudden onset of symptoms. Less severe recurrent abdominal pain and vomiting, a lower percentage of rectal bleeding and frequent diarrhoea, as well as significant weight loss were characteristic of chronic intussusception. These patients were excluded.

In the study, special attention was paid to the duration of clinical symptoms, referral of patients, the time between first presentation and the correct diagnosis and the methods of treatment. Furthermore, any complications and the rate of recurrence were investigated by clinical and sonographic re-evaluations during hospital stay. The patients were regularly seen in a specialised outpatient department 2 weeks after discharge from the hospital.

Statistical evaluation was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

Ninety-eight children with acute intussusception (60 boys and 38 girls) were treated between 1996 and 2005. The mean age of the patients at presentation was 1 year 9 months (range 2 months to 12 years). Fifty (51%) patients were younger than 1 year and 17 (34%) patients were older than 3 years. Fifty-four (55%) patients were referred from outside hospitals due to an uncertainty in diagnosis or with an established diagnosis for further treatment. Thirty-five out of these 54 patients were sent with a non-established diagnosis. Fourteen out of 54 patients were referred with suspected intussusception for further treatment. Five out of 54 patients were referred after previous treatment trials (three with air enema, two with contrast enema) in outside hospitals.

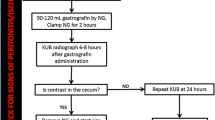

After admission, all patients underwent meticulous clinical investigation followed by ultrasound investigation. Air enema was the standard mode of treatment at our institution. Immediate surgical exploration was carried out after failed conservative treatment.

Most of the patients were admitted in early spring and summer (Fig. 1). None of the patients had recurrent upper airway infections and four patients (4.1%) had a history of chronic constipation. Feeds varied from bottle feeds to normal feeds, consistent with the age of the children. No clear relation to breast milk feeds was obvious. Eight out of 98 patients were taking antibiotics, and none of the patients had been vaccinated shortly before presenting with symptoms of intussusception.

The yearly incidence of intussusception varied considerably during the observation period (Fig. 2). The duration of clinical symptoms was 1–80 h (mean 18.9 h). We observed 25 out of 98 patients who had been experiencing symptoms for more than 24 h. The most frequent symptoms were intermittent, colicky-like abdominal pain (98%), emesis (69.4%), fever (12.2%) and bloody stools (36.7%). Other diagnoses seen at presentation were enteritis (nine cases), appendicitis (two cases), and acute respiratory tract infection (three cases).

Clinical investigation revealed a palpable, intra-abdominal tumour (31.6%), rectal blood (34.7%), and impaired peristalsis (12.2 %). Laboratory findings revealed leucocytosis in 75 cases and elevated CRP in 47 cases.

All patients underwent a primary abdominal ultrasound (axial and longitudinal scanning ultrasound and colour Doppler ultrasound). Ninety-eight patients had sonographic signs of intussusception, such as the “doughnut sign”, “target sign”, “multiple concentric ring sign” and “pseudokidney sign”.

Additional ultrasound findings were mesenterial lymphadenitis (56.8%), free intra-abdominal fluid (12.6%) and intra-abdominal mass (2.1%). Plain abdominal films were taken only in three patients to exclude free intra-abdominal air. Eleven out of the 98 patients were immediately operated on after admission due to massive rectal bleeding, severe abdominal distension, and suspected free intra-abdominal air. Spontaneous reduction of intussusception occurred in two out of 98 cases and was proven by ultrasound.

The treatment modality of choice was air enema reduction in 85 out of 98 patients (86.7%), which was successful in 66 out of 85 patients (77.6%) and failed or was not completely successful in 17 out of 85 patients (20%). Two out of the 85 (2.4%) patients did not show signs of intussusception during enema due to spontaneous reduction during preparation of the child.

Open reduction of intussusception was suggested immediately after failed conservative treatment in symptomatic patients with persistent intussusception shown by ultrasound. Twenty-eight out of 98 (28.5%) patients underwent laparotomy and manual reduction of the intussusception. Among these, 15 of the 25 patients had experienced symptoms for more than 24 h and 16 of the 54 referred patients needed an open laparotomy. Additional findings during laparotomy were malrotation (four cases; ages <1 year), Meckel’s diverticulum (four cases, ages 4–14 months), and schwannoma of the small bowel (one case, 1 year old). Small bowel resection and primary anastomosis were performed in cases of Meckel’s diverticulum and schwannoma. No intussusception was noted in one case during laparotomy due to spontaneous reduction during preparation of the child. Two patients presented with intussusception post-appendectomy. One patient presented with small bowel obstruction after the surgical correction of intussusception. No further postoperative complications were noted in our study group.

We recorded a recurrence in two patients 6 days after enema treatment. Furthermore, we had one patient with two recurrences and one patient with three recurrences, occurring four days after enema reduction. These patients were treated using enema reduction.

Altogether, 95% of the patients presented with primary idiopathic intussusception and the remaining 5% with pathological lead points (Meckel’s diverticulum, n = 4; schwannoma of the small bowel, n = 1).

Patients who had experienced symptoms for more than 24 h showed an increased rate of open surgery. Patients who were referred had the same rate of open surgery.

A significant correlation was found between a longer duration of symptoms and an increased rate of open surgery. Furthermore, a statistically significant correlation was evident between the referral patients and an increased rate of open surgery (Table 1).

Discussion

Intussusception represents the most common abdominal emergency in infancy. More than 90% of the cases are idiopathic. The remaining 10% of the cases with intussusception are secondary to Meckel’s diverticulum, polyps (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), duplications, mesenteric cysts, intramural haematoma or lymphoma [1]. Our study revealed idiopathic intussusception in 95% of cases. The remaining cases showed pathological lead points such as Meckel’s diverticulum or schwannoma of the small bowel.

An association between antibiotic drug use and intussusception was identified in a recent case–control study, which revealed that antibiotics like cephalosporin were associated with a more than 20-fold increased risk of intussusception [8]. Furthermore, the association between intussusception and the rotavirus vaccine prompted removal of the product from the market in 1999 [9]. A recently published study confirmed that the risk of intussusception did not differ significantly between different rotavirus strategies [10]. In our study, no relationship was observed between intussusception and vaccination or antibiotic treatment.

The classical clinical triad of intussusception, consisting of abdominal colic, red jelly stools and a palpable mass, is only present in about 50% of the cases, whereas up to 20% of the patients are symptom-free upon clinical presentation. This was also observed in our study. However, the incidence of the symptom triad in radiologically or surgically proven intussusception varied markedly among the published studies (range, 10–82%) [11].

The incidence of intussusception varied significantly as evidenced by the literature [12]. The incidence of acute intussusception ranged from 0.66 to 2.24 per 1,000 children in inpatient departments and 0.75 to 1.00 per 1,000 children in emergency departments in Europe [13]. A large cohort study of 1.7 million Danish children showed a substantial decrease in intussusception since the beginning of the 1990s. The decrease was mainly observed among children aged 3 to 5 months and was equivalent between boys and girls [14]. In contrast, the hospitalisation rate due to primary idiopathic intussusception marginally increased from 0.19 to 0.27 per 1,000 live births in a large Australian hospital [15]. The present study did not reveal a significant change in the incidence of intussusception during the years of observation, which may be due to the relatively small number of cases treated within our single centre.

The primary imaging technique, ultrasound, provides the diagnosis of exclusion of an intussusception, with a sensitivity of 98–100%, specificity of 88% and a negative predictive value of 100% [16, 17]. The present study confirms this data, since we used ultrasound as the primary modality for diagnosis in all the patients. The diagnostic accuracy was 100% in our study.

The reduction of intussusception with contrast enema techniques, in particular air enema, has become standard in many institutions, with success rates ranging from 75–85% [18–23]. Interestingly, the technique of air reduction of intussusception was described more the 100 years ago [22, 24]. The air enema reduction technique has been broadly used and is successful in the vast majority of cases [25]. The present study shows a success rate of 78% using air enema reduction, which may be due to the selected patient group. The long duration of symptoms and small bowel obstruction on plain radiographs are no longer contraindications to air enema reduction [26]. A further study recommends delayed and repeated reduction attempts in all patients with intussusception [27]. Interestingly, uncomplicated cases of intussusception were treated in the outpatient clinic after successful reduction, which was shown in a retrospective cohort study [28].

Surgery is indicated in cases in which the enema reduction has failed, in those where a pathological lead point is identified on an imaging study or in the presence of free air or peritonitis.

Recurrent intussusception occurs mainly in non-operated acute cases, which has been reported previously and was confirmed by the present study [29]. Repeated enemas for reduction are justified due to the low complication rate. The present study does not include patients who underwent repeated air enema reduction attempts due to the incomplete reduction in the first place.

A considerable amount of variability exists in all phases of intussusception management. This includes the identification of patients with intussusception, the influence of symptom duration on the outcome, the use of ultrasound in diagnosis and in the monitoring of the reduction attempt [1, 2, 26, 30, 31].

Our study revealed an association between the duration of symptoms and the rate of surgically treated patients. Furthermore, more referred children needed open surgical treatment compared with children who brought directly to our hospital by their parents. This was also due to a significantly longer duration of symptoms. It is obvious that the duration of symptoms displays a significant factor of morbidity for complications and, necessarily, surgical interventions. This applies for cases of acute intussusception, which were exclusively included in our study. The longer duration of symptoms may lead to increasing oedema of the bowel wall and advancing intussusception, which clearly reduces the chances of enema reduction.

Another major influencing factor is the experience in managing the various clinical presentations of intussusception. A prospective study clearly revealed that children who were treated with intussusception in a large children’s hospital had a decreased risk of operative care, a shorter length of stay, and lower hospital charges compared with children who received care in hospitals with a smaller paediatric caseload [32]. Furthermore, a comparative study revealed that the management of intussusception outside tertiary care centres is neither uniform nor standardised [33]. Another very interesting study revealed that delayed treatment in a rural area of a developing country compared with an urban hospital and a European hospital resulted in a much higher rate of mortality in terms of a laparotomy rate, intestinal necrosis and intestinal resection [34].

To reduce the number of cases that require surgery for intussusception treatment, rapid diagnosis and treatment of intussusception is essential. This depends on the early referral of affected children to experienced paediatric surgical centres. It appears that guidelines that increase the non-operative rate of intussusceptions management are needed which result in the increased awareness of the expanding indications for enema reduction, delayed repeat enemas and access to specialist paediatric surgical staff [35, 36].

Conclusion

Despite the classical history and clinical presentation, diagnosing intussusception remains a challenge for paediatric surgeons, paediatric radiologists and paediatricians. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of intussusception are related to an increased rate of surgical intervention and complications. A higher rate of surgical interventions is evident in patients who have been experiencing symptoms for more than 24 h and in referred patients. Intussusception should always be treated in specialised paediatric hospitals by an interdisciplinary team, including paediatric surgeons. Ultrasound has been proven an accurate method of making the diagnosis in intussusception.

References

DiFiore JW (1999) Intussusception. Semin Pediatr Surg 8:214–220

Stringer MD, Pablot SM, Brereton RJ (1992) Paediatric intussusception. Br J Surg 19:867–876

Linke F, Eble F, Berger S (1998) Postoperative intussusception in childhood. Pediatr Surg Int 14:175–177

Komadina R, Smrkolj V (1998) Intussusception after blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 45:615–616

Kuppermann N, O’Dea T, Pinckney L, Hoecker C (2000) Predictors of intussusception in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154:250–255

Yamamoto LG, Morita SY, Boychuk RB, Inaba AS, Rosen LM, Yee LL, Young LL (1997) Stool appearance in intussusception: assessing the value of the term “currant jelly”. Am J Emerg Med 15:293–298

Birkhahn R, Fiorini M, Gaeta TJ (1999) Painless intussusception and altered mental status. Am J Emerg Med 17:345–347

Spiro DM, Arnold DH, Barbone F (2003) Association between antibiotic use and primary idiopathic intussusception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157:54–59

Zanardi LR, Haber P, Mootrey GT, Niu MT, Wharton M (2001) Intussusception among recipients of rotavirus vaccine: reports to the vaccine adverse event reporting system. Pediatrics 107(6):97–102

Tai JH, Curns AT, Parashar UD, Bresee JS, Glass I (2006) Rotavirus vaccination and intussusception: can we decrease temporally associated background case on intussusception by restricting the vaccination schedule? Pediatrics 118:258–264

Bines JE, Ivanoff B, Justice F, Mulholland K (2004) Clinical case definition for the diagnosis of acute intussusception. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 39:511–8

World Health Organization, Initiative for Vaccine Research Department of vaccines and Biologicals. Acute intussusception in infants and children. Incidence, clinical presentation and management: a global perspective. WHO/V&B/02.19, online publication

Huppertz HI, Gabarro-Soriano M, Grimprel E, Franco E, Mezner Z, Desselberger U, Smit Y, Wolleswinkel-van den Bosch J, De Vos B, Giaquinto C (2006) Intussusception among young children in Europe. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25:S22–S29

Fischer TK, Bihrmann K, Perch M, Koch A, Wohlfahrt J, Kare M, Melbye M (2004) Intussusception in early childhood: a cohort study of 1.7 million children. Pediatrics 114:782–785

Justice FA, Auldist AW, Bines JE (2006) Intussusception: trends in clinical presentation and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21:842–846

Daneman A, Navarro O (2003) Intussusception. Part 1: a review of diagnostic approaches. Pediatr Radiol 33:79–85

Sorantin E, Lindbichler F (2004) Management of intussusception. Eur Radiol 14:L146–L154

Shehata S, El Kholi N, Sultan A, El Salwi E (2000) Hydrostatic reduction of intussusception: barium, air, or saline. Pediatr Surg Int 16:380–382

Hadidi AT, El Shal N (1999) Childhood intussusception: a comparative study of non surgical management. J Pediatr Surg 34:304–307

McDermott VG, Taylor T, Mackenzie S, Hendry GM (1994) Pneumatic reduction of intussusception: clinical experience and factors affecting outcome. Clin Radiol 49:30–34

Heenan SD, Kyriou J, Fitzgerald M (2000) Effective dose at pneumatic reduction of pediatric intussusception. Clin Radiol 55:811–816

Cohen MD (2002) From air to barium and back to air reduction of intussusception in children. Pediatr Radiol 32:74

Sandler AD, Ein SH, Connolly B, Daneman A, Filler RM (1999) Unsuccessful air-enema reduction of intussusception: is a second attempt worthwhile? Pediatr Surg Int 15:214–216

Holt LE (1897) The diseases of infancy and childhood—for the use of students and practitioners of medicine. Appleton, New York, pp 378–388

Rubi I, Vear R, Rubi SC, Torres EE, Luna A, Arcos J, Paredes R, Rodriquez J, Velasco B, Garcia M (2002) Air reduction of intussusception. Eur J Pediatr Surg 12:387–390

Beasley SW, Myers NA (1998) Intussusception: current views. Pediatr Surg Int 14:157

Navarro OM, Daneman A, Chae A (2004) Intussusception: the use of delayed, repeated reduction attempts and the management of intussusceptions due to pathologic lead points in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182:1169–1176

Bajaj L, Roback MG (2003) Postreduction management of intussusception in a children’s hospital emergency department. Pediatrics 112:1302–1307

Crankson SJ, Al-Rabeeah AJ, Fischer JD, Al-Jadaan SA, Namshan MA (2003) Idiopathic intussusception in infancy and childhood. Saudi Med J 24:S18–20

Navarro O, Dugougeat F, Kornecki A, Shuckett B, Alton DJ, Daneman A (2000) The impact of imaging in the management of intussusception owing to pathologic lead points in children: a review of 43 cases. Pediatr Radiol 30:594–603

Klein EJ, Kapoor D, Shugerman RP (2004) The diagnosis of intussusception. Clin Pediatr 43:343–347

Bratton SL, Haberkern CM, Waldhausen JHT, Sawin RS, Allison JW (2001) Intussusception: hospital size and risk of surgery. Pediatrics 107:299–303

Calder FR, Tan S, Kitteringham L, Dykes EH (2001) Patterns of management of intussusception outside tertiary centers. J Ped Surg 36:312–315

van Heek NT, Aronson DC, Halimun EM, Soewarno R, Molenaar JC, Vos A (1999) Intussusception in a tropical country: comparison among patient populations in Jakarta, Jogyakarta, and Amsterdam. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 29:402–405

Reid R, Kulkarni M, Beasley S (2001) The potential for improvement in outcome of children with intussusception in the South Island. N Z Med J 114:441–443

Somme S, To T, Langer JC (2006) Factors determining the need for operative reduction in children with intussusception: a population based study. J Pediatr Surg 41:1014–1019

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lehnert, T., Sorge, I., Till, H. et al. Intussusception in children—clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Colorectal Dis 24, 1187–1192 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0730-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0730-2