Key Points

-

Discusses key ethical and legal principles of informed consent.

-

Outlines core professional standards for the practice of informed consent in dentistry.

-

Discusses the concept of shared decision-making in dental practice.

-

Relates the outcomes of a recent legal case to dental practice.

Abstract

All healthcare professionals are required to gain a patient's consent before proceeding with examination, investigation or treatment. Gone are the days when consent was about protecting the professional. Following a recent landmark Supreme Court case, 'informed' consent is now embedded in UK law. Patients have the right to high-quality information that allows them to be involved in making decisions about their care. Dentists have a duty of care to provide this information and guide their patients through the process. This paper reviews key ethical, legal, and professional guidance available to dentists about informed consent and concludes by discussing how shared decision-making is a model of healthcare delivery with much to offer dentist and patient alike.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All healthcare professionals are familiar with consent. It is the ethical, professional and legal obligation to gain a patient's authorisation before performing a treatment or investigation. Respecting a patient's right to autonomous choice underpins the ethical dimensions of consent. Professional regulatory bodies provide guidance on how dentists should guide patients through the consent process, while the law is primarily concerned with the adequacy of information disclosure during consent consultations. There is evidence, however, that professionals often view obtaining consent as a procedural formality.1 If so, the process may fail to meet ethical and professional requirements. A recent landmark case has seen the law better match these guidelines, and now sets-out clear standards of communication required to prepare patients for treatment. This paper provides an overview of the key ethical, professional, and legal aspects of informed consent in the United Kingdom, with an emphasis on what recent changes in the law mean for the dental team.

Ethics and consent

Of the four guiding principles in biomedical ethics – beneficence, non-malificence, justice, and autonomy – the latter has dominated modern theories and models of informed consent.2,3 In the past, paternalism ruled. Surgeons and other healthcare providers, seemingly acting out of beneficence, chose what to disclose or not disclose about an operation or procedure. The assumption was that too much information would cause patients undue anxiety or distress, and that doctors and dentists knew best. As early as 1914, however, there was recognition that patients had a right to know what was going to happen to them.4 Since the middle of the last century, an increasingly consumerist society, at least in the Western world, has been paralleled by a realisation of a patient's right to self-determination. Assuming the patient has decision-making capacity, this means respecting a patient's autonomy about what happens to his or her body.5 This autonomy should, however, be rational and balanced against other bioethical principles.6 In publically-funded health systems like the NHS, for example, limited resources may mean choices have to be made within certain constraints. Fully autonomous decision-making is likely to be undesirable and unattainable, but treatment decisions are ideally based on the patient's wishes or goals, with additional support from scientific evidence and clinical opinion.6,7 Accepting these conditions, the ethical principle of autonomy has become increasingly important in how consent to invasive treatment or investigation has been viewed by the law courts in the UK and elsewhere.

The law and consent in the United Kingdom

The right to self-determined protection of bodily integrity is central to the legal understanding of consent.8 To authorise surgery or other intervention that breaches that integrity, patients need information, and it is part of a dentist's duty-of-care to his or her patients to provide it.9 Failure to provide sufficient information could, in the event of an adverse clinical outcome, constitute a negligent failure of this duty.10 But how much information should be disclosed to avoid this, and to ensure that patients are sufficiently prepared for surgery and its outcomes? The courts' views on what constitutes adequate information are subject to change because new standards are set as case law changes. A doctrine of informed consent has not existed in UK law, although that may be changing. In treating a cognitively competent person without first obtaining appropriate informed consent, a dentist could be guilty of common assault or battery under criminal law.11 By providing consent, the patient waives these legal rights and allows actions to be performed that would otherwise not be permissible in law. In cases where there is a dispute over whether or not consent was given, patients tend to seek remedy via tort in the civil courts. This would be undertaken with the aim of receiving financial compensation for any damage or loss caused rather than seeking to prosecute with a criminal conviction. Whether a clinician has been negligent in such cases would be decided by asking questions about the materiality of information about a given risk.12 That is, from whose perspective should decisions about whether or not something should have been disclosed be made? To illustrate this concept, it is useful to summarise key historic landmark cases before considering what the ruling about materiality in a recent case means for the practice of gaining patients' consent.

Bolam, Sidaway, Pearce and Chester

In 1957, the Bolam case established the concept of the 'prudent doctor'.13 Mr Bolam suffered limb injuries during electroconvulsive therapy for treatment of his depression, the risk of which had not been disclosed before treatment. His attempt to sue the hospital was unsuccessful because the judge ruled that the psychiatrist had 'acted in accordance with a practice accepted by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that art'.13 The extent to which information should be disclosed was viewed as part of a clinician's professional repertoire alongside diagnostic and management skills. The paternalistic 'Bolam test' thus established stood unmodified for almost 30 years until Sidaway in 1985.14 Although the House of Lords stated that a clinician should take reasonable care to advise the patient of any material risk, Mrs Sidaway, who was left paralysed after spinal surgery, unsuccessfully sued because, essentially, the Bolam test was upheld, even in light of the risk of the complication being approximately 1–2%.14 It should be noted, however, that Lord Scarman's dissenting opinion that patients should ordinarily be warned of material risks may have heralded the turn against paternalism in the UK courts.

A further modification in the law came with Chester vs. Afshar which ruled that the claimant (patient) need not demonstrate that the resultant harm was due to the failure to disclose.15 This is the legal principle of causation, and in the context of Chester means that, even if the patient had been informed of the risk, it was not incumbent on her to prove that she would not have proceeded with the surgery.10 In Pearce, the patient did not prove that an obstetrician's failure to disclose the risk of still birth was negligent, but the Court of Appeal did assert that, when asked of a risk, the 'reasonable doctor' was required to tell the patient what the 'reasonable patient' would want to know.16 The Pearce and Chester cases have informed much of the present-day guidance on informed consent from the professional bodies, which set-out standards seemingly above-and-beyond those required in law until a recent ruling by the Supreme Court.

Montgomery

This 2015 ruling states an important change in the way the courts have ruled on the materiality of information. Mrs Montgomery, a pregnant diabetic woman, was not warned by her obstetrician about the increased risk of the baby's shoulder getting stuck in the birth canal during labour, or advised about possible alternatives, including caesarean section.17 Unfortunately, this complication occurred and the baby boy suffered brain hypoxia and subsequent disability. Mrs Montgomery contested that she should have been warned of her elevated risk of this complication and would have opted for delivery by caesarean section if she had been given the option. In court, her obstetrician argued that, had she warned every diabetic woman of this risk, they would all request elective caesarean section, perhaps unnecessarily. In their ruling, the Supreme Court judges did not accept the doctor's argument, stating that it is for the individual patient, and not for the doctor or medical establishment, to decide upon the materiality of a risk.17 This is the key outcome from Montgomery. The Bolam test no longer stands and clinicians must determine the materiality of a risk by either asking whether a reasonable person in the patient's position would be likely to attach significance to the risk; or the clinician should reasonably be aware that the patient would likely attach significance to it.17,18,19 Applying rules about disclosure of a risk based on percentages of occurrence is no longer acceptable. The meaning of that complication to the individual patient is what is important.

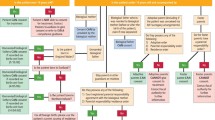

While Montgomery has important implications for all clinicians, as summarised in Table 1, it is important to realise that in the UK professional and regulatory bodies have set-out guidelines for the practice of obtaining consent which long pre-date this ruling. As will be seen in the next section, they describe requirements that go beyond the legal understandings of consent by providing frameworks for patient-centred decision making.

Professional guidance on consent

In the UK, the Royal College of Surgeons of England, the General Dental Council (GDC), the General Medical Council (GMC), and the Department of Health have all compiled guidance on standards of practice expected of clinicians with regard to informed consent.9,20,21,22 In these guidelines, consent is described as a process requiring time, patience, and clarity of explanation about the treatment and possible alternatives, risks and expected outcomes. There are explicit statements about consent not being 'merely the signing of a form'.20 Consent is described as 'informed decision making' that requires a partnership between clinician and patient.9,20

Of interest to some dentists, supplementary professional guidance has been prepared on standards for cosmetic procedures.23,24 Here, clinicians are required to allow a 'cooling off' period of two weeks between the consent consultation and surgery. In these situations, consent may be viewed as an 'informed request' because the patient has usually sought-out the treatment, but the requirement for careful explanation of the expected outcomes, potential risks, and alternative treatments is the same.

These guidelines, and the recent changes in the law described above, all align consent more closely with the concept of shared decision-making. The next section will review this model of doctor-patient communication, with particular emphasis on its application in surgery.

What is shared decision-making?

Shared decision-making is the collaborative deliberation about treatment options between clinician and patient.25 It is a key component of patient-centred care and is gaining prominence as the preferred model for communication in healthcare encounters.25 There are clinical scenarios where shared decision-making is not required or appropriate. In medicine, for example, giving aspirin to a patient suffering a myocardial infarction, or starting antibiotics immediately in suspected meningitis are examples of 'effective care', where there is little to weigh-up in terms of risks, benefits, and outcomes.26 In dentistry, extraction of an unrestorable tooth that is the source of an abscess, or biopsy of a suspicious lesion might be examples but it is important to remember that, in all these cases, the patient has the right to refuse intervention if they have the capacity to do so.

'Preference sensitive care', on the other hand, describes those situations where the benefits and risks of any given treatment or alternative option are less clear-cut.26 Decision aids exist, for example, to help clinicians and patients decide about treatment in some circumstances.27,28 These decision aids are time and labour intensive to produce, but are intended to provide an evidence-based framework on which the consultation can be based. They require good-quality evidence from, for example, randomised controlled trials and meta analyses, on which information about prognosis and risk can be provided.27 Decision-aids are not, as yet, widely available in dentistry but the principles of shared decision-making can be applied to most consultations. For instance, whether to restore a tooth with a filling or crown; whether or not to proceed with orthodontic treatment; whether to restore an edentulous space with a partial denture or implant-based prosthesis are all examples of preference-sensitive care. In dentistry, additional consideration must also be given to the financial implications of any given treatment. Early evidence about shared decision-making appears to show it has a role in addressing geographic differences in the provision of care, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment.29 Further work will be required to investigate how best to apply these principles in dentistry but it is likely that this model of delivering healthcare, which is already embedded in policy in the UK and abroad, will become the rule and not the exception.

Summing up - What do the changes mean for dentists?

While the Montgomery case brings a much-needed update to the law, it is possible that most clinicians are already practising to these standards. By following guidance from professional bodies including the GDC, dentists will be aware of the need to carefully explain the potential risks and benefits associated with treatment options. Allowing patients the time to consider these options and ask questions is important. The case does, at least, serve as a timely reminder of these principles. It aligns with modern healthcare delivery policy; emphasises that the consent form is not proof that the patient has been informed, or has understood what has been discussed; and affirms the legal recognition that materiality 'belongs' to the patient and not the healthcare professions.

References

Wood F, Martin S M, Carson-Stevens A, Elwyn G, Precious E, Kinnersley P . Doctors' perspectives of informed consent for non-emergency surgical procedures: a qualitative interview study. Health Expect 2014; DOI: 10.1111/hex.12258 [e-pub ahead of print].

Beauchamp T L, Childress J F . Principles of biomedical ethics. 6th ed. pp 99–140. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Faden R R, Beauchamp T L . A history and theory of informed consent. pp 307–309. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospitals 211 NY 128, 105 NE 93 (1914).

Grady C . Enduring and emerging challenges of informed consent. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 855–862.

O'Neill O . Some limits of informed consent. J Med Ethics 2003; 29: 4–7.

Main B et al. Bringing informed consent back to patients. Available online at http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2014/08/05/barry-main-et-al-bringing-informed-consent-back-to-patients/ (accessed September 2015).

Brazier M, Cave E . Medicine, patients and the law. 5th ed. pp 64–65. London: Penguin, 2011.

General Dental Council. Principles of patient consent. London: GDC, 2009.

Herring J . Medical law and ethics. 2nd ed. pp 92–132. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Criminal Justice Act 1988, s39.

Dire C . Doctors must not cherry pick information to give patients, landmark case determines. BMJ 2015; 350: h1414.

Bolam v. Friern HMC [1957] 2 All ER 118.

Sidaway v. Bethlem Royal Hospital Governors [1985] AC 871.

Chester v. Afshar [2004] UKHL 41.

Pearce v. United Bristol Healthcare NHS Trust [1999] 48 BMLR 118.

Montgomery v. Lanarkshire Health Board (Scotland) [2015] UKSC 11.

Sokol D . Update on the UK law on consent. BMJ 2015; h1481.

Sutherland L . Montgomery in the Supreme Court: a new legal test for consent to medical treatment. Scottish Legal News. Available online at http://www.scottishlegal.com/2015/03/12/montgomery-in-the-supreme-court-a-new-legal-test-for-consent-to-medical-treatment/ (accessed September 2015).

Good surgical practice. The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2015. Available online at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/surgeons/surgical-standards/professionalism-surgery/gsp (accessed September 2015).

The General Medical Council. Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together. London: GMC, 2008.

Department of Health. Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment. Available online at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138296/dh_103653__1_.pdf (accessed September 2015).

Royal College of Surgeons. Professional standards for cosmetic practice. Available online at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/publications/docs/professional-standards-for-cosmetic-practice (accessed September 2015).

General Medical Council. Press Release. Give patients time to think before cosmetic procedures, doctors told. Available online at http://www.gmc-uk.org/news/26550.asp (accessed September 2015).

Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds). Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. pp 3–9. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Mulley A, Trimble C, Elwyn G . Patients' preferences matter. Stop the silent misdiagnosis. London: The King's Fund, 2012.

Agoritsas T, Fog Heen A, Brandt L et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision-making: the pace quickens. BMJ 2015; g7624.

O'Connor A M, Edwards A . The role of decision aids in promoting evidence-based patient choice. In Edwards A, Elwyn G (eds). Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. pp 191–200. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Malhotra A, Maughan D, Ansell J . Choosing wisely in the UK: the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges' initiative to reduce the harms of too much medicine. BMJ 2015; h2308.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Main, B., Adair, S. The changing face of informed consent. Br Dent J 219, 325–327 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.754

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.754

This article is cited by

-

How-to-do: Weisheitszahnentfernung

wissen kompakt (2024)

-

Considerations for restorative dentistry secondary care referrals - part 1: defining strategic importance

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Contemporary management of advanced midface malignancy in the age of Instagram - a parallel surgical and patient's perspective

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Evaluation of the information provided by UK dental practice websites regarding complications of dental implants

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Systematic Review of Innovation Reporting in Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty

Obesity Surgery (2021)